A film or television tie-in can not only give you the story of the movie, it can give an additional amount of description to fill in of some of the blanks, and help flesh out the characters.

Here are some of the novels that have either inspired film in which Peter appeared, or are direct tie-ins. As you will see, there are often quite a number of differences between the two which have been highlighted.

Film The Siege of Sidney Street

- Title: The Siege of Sidney Street

- Author: Frederick Oughton

- Published by: Pan Books

- Date of Publication: 1st January, 1961

- Number of Pages: 188

- Country of Origin: UK

The real life event of 1911 are transformed into a tale of a devoted police officer who becomes part of a love triangle with a gangster and his girlfriend, and the gang of Russian anarchists that rob and murder – not for self, but for the ideology that drives them on.

A good proportion of the novel is devoted to Mannering’s investigation around the social club where the Russian immigrants meet. His enquiries lead him to talk with the landlord of the pub opposite the club who tells the detective: “It’s a club alright! God, you can hear them jabbering’ away – fifty to the dozen – right down the perishing street. Club they calls it! Whore house more like! God, you should hear them. I’ll tell you something else too. All they drinks there is tea. Tea. Round here folks say as they’re vegetarians.“

“Perhaps they don’t like meat, that’s all,” says the detective.

“Meat?” replies the landlord “Who said anything about meat? Vegetarians, that’s what I said. That or them anarchists. Wouldn’t be surprised to hear they was atheists too. Tell you, that club’s got a bit of a name round this district, sir.“

Vegetarians! And atheists to boot! How brilliant is that?

Taken from the back of the book: ‘The Day Anarchy Clutched At London. London’s East End – January 3rd 1911. Bullets whine in Sidney Street, holding back hundreds of police, guardsmen and the Home Secretary – Winston Churchill. Three anarchist fanatics – Peter the Painter, Yoska, Svaars – had robbed and killed for their cause. Now had come the bloody day of reckoning… Here is a sensational story with a scaffolding of truth – of the gaslit, gin-soaked era when marauding anarchists took whatever they could grab.’

The Differences:

- The book tells us that Peter Piatkow (A.K.A. Peter the Painter) is a pipe smoker, having taken to smoking to appear “more English”.

- After leaving Russia, Peter had intended to go to Paris, but due to the political jostling there, he chose London instead.

- On his arrival in England, Peter had first lived in the Hyde Park area of London, before taking rooms in the East End.

- His first love had been Nina, played by Angela Newman in the film, and had considered proposing marriage to her.

- Sara (Nicole Berger in the film), is said to have had many lovers but had never been in love until meeting Peter.

- The book describes Peter as loving as he lived – for the accusation of a prize: “His lovemaking was almost harsh, burning up like magnesium.” He encourages Sara to resist him so that he might eventually “conquer” her.

- In the book, Sara, dies without knowing that Peter has escaped the fire in the house on Sidney Street, but in the film, she lives to see him make his escape.

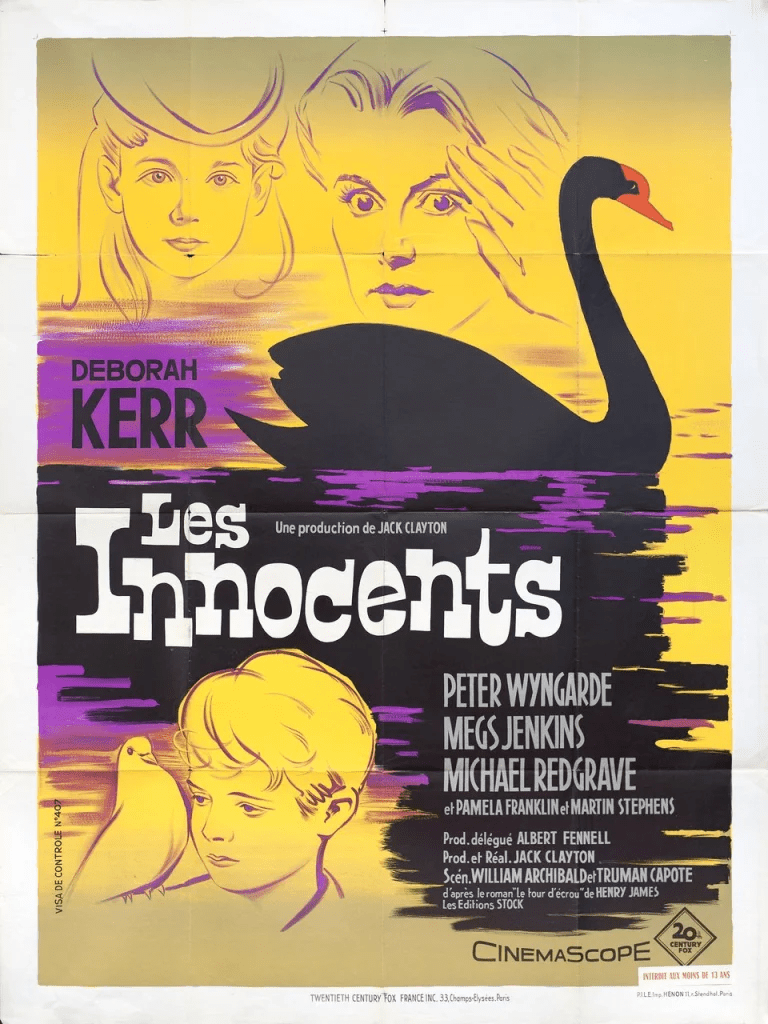

Film Turn of the Screw and The Innocents

- Title: The Siege of Sidney Street

- Author: Henry James

- Published by: Penguin

- Date of Publication: 16th April, 1898

- Number of Pages: 121

- Country of Origin: UK

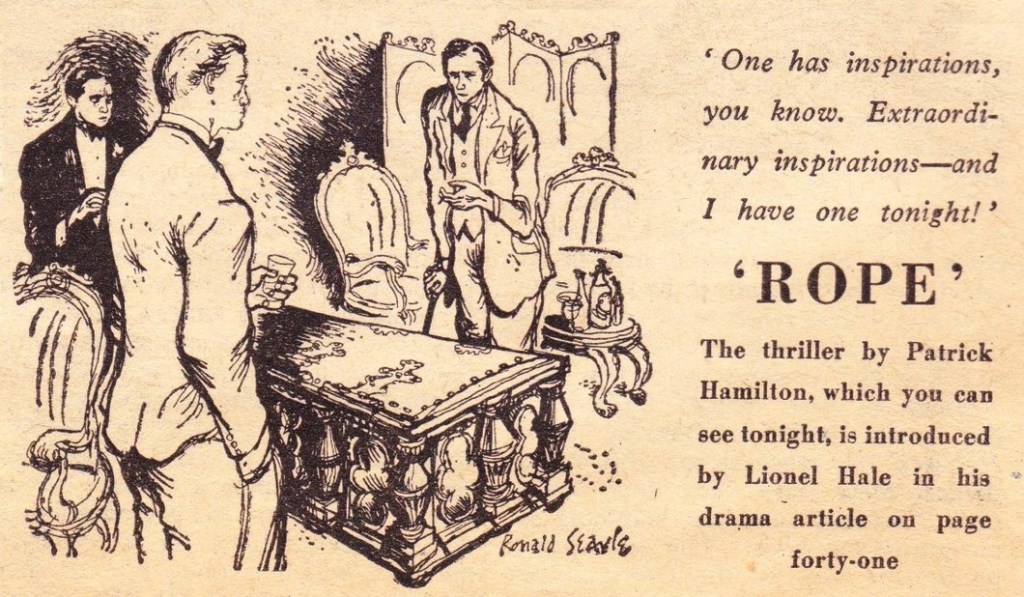

Author, Henry James, once said that ‘The Turn of the Screw’ began as a “shadow of a shadow.” In 1895, a story was told to him by the Archbishop of Canterbury about “a couple of small children in an out-of-the-way place, to whom the spirits of certain ‘bad’ servants, dead in the employ of the house, were believed to have appeared with the design of ‘getting hold’ of them.” Three years later, the 1st chapter of ‘The Turn of the Screw’ was published in an American magazine entitled, Collier’s Weekly. In 1950, the characters of Peter Quint and Miss Jessel appeared in another form in William Archibald’s play, The Innocents. Four years later, the two servants would be resurrected again in Benjamin Britten’s opera, but perhaps their most well-know incarnation would be in Jack Clayton’s classic 1961 film – also called The Innocents, in which Peter Wyngarde was to play the evil spectre, Peter Quint.

On the surface, the plot of the film is relatively simple. A governess (Deborah Kerr) is employed to care for two young children named Flora (Pamela Franklin) and Miles (Martin Stephens) at a lonely manor house called Bly. She begins seeing the ghosts of the former governess Miss Jessel (Clytie Jessop) and valet, Peter Quint. According to housekeeper, Miss Grose (Megs Jenkins), the two had been having a sordid affair under the noses of the children (it is implied that they had been witnessed by Miles and Flora having sex in front of the fire in the drawing room). Miss Giddens becomes convinced that the children are in some way in touch with the ghosts, so her mission is now to rescue them from the spirits influence by getting them to admit that they are haunted by Miss Jessel and Peter Quint.

The Differences:

- The differences between the film and the novel can be summed up this way: The Turn of the Screw is a complex psychological drama that features ghosts. – The Innocents – A ghost/haunted house story with psychological underpinnings.

- The Turn of the Screw begins with a group of friends who are gathered on Christmas Eve night to listen as someone recites a ghost story. The film, however, opens with a young governess visiting the office of her well-to-do employer in, we presume, London.

- In the book, the governess remains unnamed throughout the story, but in the film she’s given the name, Miss Giddens.

- The spectre of both Miss Jessel and Peter Quint are omnipresent throughout the book, but only appear occasionally in the film.

- When the governess sees either Jessel or Quint, but the other characters claim not to see them, the ghosts are on screen. From the camera’s perspective, the ghosts are there – they exist, and the other characters, in denying their presence, could well be seeing them but lying about it. In the book, however, the text presents the governess’s in such a way that there is evidence both for and against her. Without the vindication of her own narrative, her paranoia and perceptible anxiety, in addition to her tendency to jump to complex conclusions, become increasingly obvious. Otherwise, the film plays up the children’s peculiarities enough so that her conjecture that they’re possessed could be possible. The behaviour of them while at play, could be seen as malicious.

- The most significant way in which the film preserves book’s ambivalence is in the way it visually projects the subtext of the governess’s mental or emotional attitudes towards sex. Director, Freddie Francis, skillfully preserves the novella’s subtlety concerning this facet of the story. That said, it’s clear that there is something questionable about Miles, not least when he passionately kisses the adult governess.

- Miss Gidden’s discusses her family in both in the book and in the film; mentioning that her father is a stern church minister. Her family home, where she had lived until moving to Bly, she describes as being small – certainly “too small for secrets.”

- The nature of Quint and Jessel’s supposed malevolency is never fully defined, either in the book or the film. Henry James wrote in the preface to the New York Edition of the story in 1908: “What, in the last analysis, had I to give the sense of? Of their being, the haunting pair, capable, as the phrase is, of everything – that is of exerting, in respect to the children, the very worst action small victims so conditioned might be conceived as subject to.” Only make the reader’s general vision of evil intense enough . . . and his own experience, his own imagination, his own sympathy (with the children) and horror (of the false friends) will supply him quite sufficiently with all the particulars. Make him think the evil, make him think it for himself, and you are released from weak specifications.” This is exactly what happens to the reader of The Turn of the Screw, and it is also, in a sense, the experience of the governess, who thinks the evil for herself with an imaginative ferocity that becomes, over a long country summer, a malignity of its own.

- To a extraordinary degree The Innocents succeeds in replicating on the screen the author’s play of perception: it makes us – the viewer – question what we see, and amplify what we imagine. The film is in black and white, which has always been an excellent medium for a ghost story. CinemaScope also leaves a lot of empty space for us to fill with dark conclusions and images, which is just what the author wanted. Most ghost stories are claustrophobic. The Turn of the Screw is meant to grow in the fearful minds of its audience. It does so in both the film and the book.

- In the final scene in which Miles dies in Miss Gidden’s arms: This takes place in the house itself in the book, but in the film, the piece is played out in the garden with what appears to be the figure of Peter Quint standing amongst the statues.

Click below for more about The Innocents…

Film Conjure Wife and Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn

- Title: Conjure Wife/Burn Witch Burn

- Author: Fritz Leiber

- Published by: Berkley Medallion Corporation

- Date of Publication: 1st April, 1943 (Reissued as ‘Burn Witch Burn’ in 1962)

- Number of Pages: 176

- Country of Origin: USA

While Fritz Lieber’s Conjure Wife was not a film tie-in; it was, in fact, written in 1943 – almost 20 years prior to the release of Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn – it was reissued in 1962 in the USA with a cover featuring a representation of Peter and his screen wife, Janet Blair.

Conjure Wife was first published (in a shorter form) in ‘Unknown’ magazine and as a single book 10 years later in 1953. The setting for the novel was New England, USA, while this was changed to rural England.

It does – as he steps into his wife’s dressing room on a whimsy and goes randomly through her drawers, and discovers that she is a witch.

What makes the story works so well, in addition to smooth writing and engaging characters, is Leiber’s careful management of Norman’s attitude. He’s forced to weigh whether magic really exists, or the events of the story are complex and unconscious psychological constructs. Reason pushes him one way, while the need to save his beloved wife pushes in another.

Leiber’s plots are always unique and this short novel is no exception. Norman Saylor and his beautiful young wife Tansy are residents of a small academic township in America, in whose college Norman is a professor. He is unconventional and disliked by the college’s conservative intelligentsia, but has still somehow managed to climb to the top: Tansy, looked down upon by the professors’ prim wives, has also managed to survive and become quite popular. Norman is happy about it, a bit too pleased with himself, one can say – we meet him at the beginning of the novel in a moment of perfect contentment which feels too good to be real, and which he feels must pass, as such moments are too good to last.

The Differences:

- In the novel, Norman’s surname is ‘Saylor’, while in the film, he is ‘Taylor’.

- Norman discovers that his wife is a witch within the opening to pages of the book, while in Night of the Eagle (by sneaking a look around her “dressing room” [read walk-in wardrobe] while she’s out of the house). In the film, however, it’s later on – after the game of Bridge with his colleagues from the college.

- For the script of Night of the Eagle, Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont strip back the more Leiber’s book which, for many, was much to the film’s advantage. In the book, ALL of the college wives are engaged in witchcraft, whereas in the film only Flora Carr (Margaret Johnson) and Tansy Taylor are.

- Having been written in 1943, Norman Saylor’s language, thoughts and opinions concerning woman are of that age. By 1962, Norman Taylor are, thankfully, updated.

- The inanimate stone gargoyles of Hempnell Collage, New England, become the animated stone eagle of Hempnell, UK, in the film.

- Further stripping by Matheson, Beaumont and director Sidney Hayers a level that was not in the Fritz Leiber story and tell Night of the Eagle as a psychological horror story not unrelated to the work of producer Val Lewton in the 1940s, such as Cat People, I Walked Like A Zombie and The Seventh Victim.

Click below for more about Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn…

Film Flash Gordon

- Title: Flash Gordon

- Author: Arthur Byron Cover

- Published by: Jove Books

- Date of Publication: 1st January 1980

- Number of Pages: 220

- Country of Origin: USA

- Title: Flash Gordon

- Author: Arthur Byron Cover

- Published by: New English Library

- Date of Publication: 1st January 1980

- Number of Pages: 220

- Country of Origin: UK

Ming the Merciless! He rules the planet Mongo with cold terror – and if he has his Imperial way, will conquer the entire universe! But first the king of Mongo must destroy Flash Gordon, the fair-haired earthling and Superbowl star, destined to challenge his sinister forces… together with Doctor Zarkov and the beautiful Dale Arden, Flash is sent hurdling through interstellar space to the Towers of Mingo City, the heartless armies of the all-seeing secret police, and the deadly creatures and half-human beings lurking in Ming’s lair. There, the space hero has a triple-task: survive Ming’s onslaught, free his own friends, and save – billions of light years away – the planet Earth!

The Differences:

- In there book there are several ‘Interludes’ in which the reader is updated on what effect Ming’s attack is having on the earth.

- During the first meeting of the Earthling’s with Ming in the great hall of the palace, the Emperor is said to be displeased with the conduct of the Minister of Propaganda and wishes him to be executed. It is Klytus that speaks up on the elderly Minister behalf – reminding Ming that, “Until now, he has performed his duties well.” The Emperor yields and allows the old man to live.

- Klytus is described in the novel as being approximately 5 feet, five inches tall.

- In the film, Klytus wears a powerful ring that he uses to remove the metal helmet Flash Gordon is forced to wear in the Palace dungeon. In the book, however, the General has a small gadget which he keeps in a pocket in his robes.

- While the film leads us to believe that Klytus and General Kala are and ‘item’, the book says otherwise; that they are in fact rivals.

- We learn from the book that Dale Arden is a black belt in Karate.

- The book tells us that Klytus had been seriously injured while attempting to increase his intelligence using the same Mind Altering Probe used to empty Dr. Zarkov’s mind. His face and right arm had been badly burned, which resulted in him having to wear the mask and metal plating to his arm.

- Klytus’s “sexual drives” are said to have been increased as a result of the incident with the Mind Altering Probe.

- We learn that Ming has other children aside from Princess Aura. She, as the oldest, is in line to take over from her father upon his death.

Click below for more about Flash Gordon…

TV Jason King

- Title: Jason King

- Author: Robert Miall

- Published by: Pan Books

- Date of Publication:

- Number of Pages:

- Country of Origin: UK

During the height of ‘Jasonmania’ back in 1972, Pan Books published two novels by Robert Miall entitled ‘Jason King’ and ‘Kill Jason King!’ – both of which were described on their covers as being “Based upon the successful ATV television series starring Peter Wyngarde“, and which were basically re-writes of a selection of four episodes from the series.

The first of the duo, ‘Jason King’, follows the exploits of the inimitable scribe as he adopts the guise of Vershinin Miklos – a Bulgarian master crook, who is sent undercover by Whitehall in an attempt to infiltrate an international crime syndicate who have successfully eluded the watchful eye of Scotland Yard with their computer wizardry.

Having been blackmailed by Rylans with the threat of being turned over to Her Majesty’s Inspector of Taxes, Jason makes the most of the situation by eating, drinking and making merry with Jan, one of the gang’s female companions.

The story deviates only slightly from the original which was penned by Tony Williamson for the episode. ‘A Deadly Line in Digits’, and seems to flow quite naturally into a somewhat raunchier version if, ‘Chapter One: The Company I Keep’, in which we find our hero believing that he’s developed the powers of ESP overnight when, in fact, he has merely been set up by the beautiful yet deadly Countessa Arabella do Maggiore.

In Maill’s rendition of Donald James’ original screenplay, there are a number of minor adjustments – most noticeably, the absence of the rutting rhino in the opening ‘scene’ and, sadly, there’s no nuns habit. But Jason certainly makes up for their absence by his antics with the Contessa, which are only touched upon superficially on screen, but leave little to the imagination in print!

- Title: Kill Jason King

- Author: Robert Miall

- Published by: Pan Books

- Date of Publication:

- Number of Pages:

- Country of Origin: UK

The second of the two books, ‘Kill Jason King!’, encompasses the episodes ‘As Easy As A.B.C.’ by Tony Williamson, and ‘A Red. Red Rose Forever’ by Donald James; the latter of which quite outshines the former, which as I am sure anyone who had seen the live-action story on screen will testify.

In the first segment of the book, Jason finds himself the prime suspect following a series of crimes which have in fact been perpetrated by two upper-crust villains by the names of Charles and Edward, who have taken to recreating incidents as described in Jason’s Mark Caine novels.

Matters take a drastic turn for the worst when a security guard is shot and killed during the course of one of the robberies, and a considerable fortune in platinum bullion mysteriously turns up in the boot of Jason’s car. All hope appears lost when Arlene – Jason’s beautiful bedtime companion (and only alibi!), is kidnapped by the two bounders, leaning poor J.K. with little hope of proving his innocence.

The unlikely combination of Adolf Hitler, a Swiss Bank vault and a pretty air hostess lead to yet more intrigue, adventure and romance for Jason who, as always, manages to outwit the bad guys and get the girl!

It was a very good year for villains...

a good year for blondes, diamonds and furs in London...

for brunettes, orgies, blackmail and murder in Rome...

for redheads in St Moritz.

A bad year for Department S - until his past caught up with Jason King.

The security guard was cold. Cold as the Vienna morgue where he lay. Arlene, blonde and sultry, had been kidnapped. A fortune in platinum filled the car boot. The latest haul in a series of daring robberies that stretched from Munich to Barcelona. And Jason King found himself Europe’s number one police suspect. The only suspect…

Both titles were best sellers in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada.

Click below for more information on Jason King…

TV Doctor Who

- Title: Doctor Who – Planet of Fire

- Author: Donald Cotton

- Published by: New English Library

- Date of Publication: 1987

- Number of Pages: 128

- Country of Origin: UK

The Doctor is enjoying the sun on a holiday island – but things are soon hotter than he bargained for.

The young American Perpugilliam Brown brings to the TARDIS a mysterious object that her archaeologist step-father has found in a sunken wreck. Kamelion, the Doctor’s robot friend of a thousand disguises, reacts to the object totally unexpectedly, with bewildering consequences for the TARDIS crew.

For Kamelion sends the Doctor and his friends to Sarn, a terrifyingly beautiful planet of fire. This strange world provides the key to Turlough’s secret past — and once again the Doctor is pitted against the wily Master.

The Differences:

- The description of Sarn and the site of Howard’s dig is clearly in Greece or Cyprus rather than in the Canary Islands.

- The Chief Elder, Timanov (Peter Wyngarde) is described in the book as being around 70-years old, while in the episodes he is said to be “As old as the mountain itself”.

- In the book, Timanov is portrayed to be far more understanding of his younger charges and less fanatical.

Click below for more on Doctor Who: Planet of Fire