ABC Armchair Theatre

Episode: Night Conspirators

Broadcast: Monday, 6th May 1963

Presented by Sy S Stewart and Malcolm Fraser: Regional Tour, May 1963

Regional Tour. May 1963.

The following review is based on the television presentation of Robert Muller’s controversial play, which was originally broadcast as an Armchair Theatre production in 1962. The play was performed on stage in London in 1963 with a slightly different cast – both of which are listed below.

Television Production Cast

Werner Loder – Peter Wyngarde

Marianne – Patricia Haines

General Otto von Schiltz – Ralph Michael

Karl-Hines Fessel – Wolfe Morris

Franz von Markheim – John Robinson

Dr. Wolfgang Himmermann – Cyril Luckham

The Ambassador – Ronald Leigh-Hunt

Carla – Sally Home

Adolf Hitler – Peter Arne

Adam – James Chase

Stage Cast

Werner Loder – Peter Wyngarde

Marianne – Patricia Haines

General Otto von Schiltz – Peter Vaughan

Karl-Hines Fessel – Wolfe Morris

Franz von Markheim – John Robinson

Dr. Wolfgang Himmermann – Cyril Luckham

The Ambassador – Ronald Leigh-Hunt

Carla – Sally Home

Adolf Hitler – Patrick Troughton

Adam – James Chase

The Place: Berlin. The Time: Tonight...

The Latinian Ambassador has not been sleeping well; something heavy has been weighing on his mind. Something that he so desperately needs to share.

In a secluded room in the Embassy, he stands anxiously by the window – his wife, Carla at his side, he awaits the powerful guests with whom he intends to share his deadly secret.

Across the street in a deserted warehouse hides a shadowy figure, who peers who peers down on the entrance to the Embassy building through a broken window pane. A car arrives and from it a high-ranking German Army officer steps out, who we learn is General Otto von Shiltz of the Bundeswehr’s Third Zone Command. A outspoken critic of the West, he was awarded the Iron Cross in 1942, and was said to have been a regular speaker at SS rallies before and during the Second World War.

The next individual to arrive is Franz von Markheim who, prior to 1939, was one of Germany’s foremost shipbuilders. During the War, he had turned his skills to the building of U-boats, but in 1947, he was convicted of War Crimes. Today, he is once again one of Germany’s leading industrialists, but tomorrow… who knows!

Third in this procession is the unmistakeable figure of Dr. Wolfgang Himmermann – the Archbishop of Ruhraphalia. As a crony of the powerful and friend of the rich, he had recently fought and won a libel case against one of Germany’s most respected newspapers, when it had accused him of a social scandal. It was rumoured that he’d donated the money he had been awarded in compensation to his favourite charity: The Fighting Fund of the German Nationalist Union.

Twenty-five years ago, wearing the brown shirt of the Hitler Youth, was Karl-Hines Fessel – now minister of national Rehabilitation, and fourth to arrive. Highly thought of in Washington and decorated for bravery by the French, Fessel is however greatly mistrusted in London.

The fifth and final guest is Werner Loder – a young newspaper publisher, who appears to be the only figure amongst the elite gathering who’s aware that he’s being watched from the warehouse window. Tipping his hat as if in acknowledgement, the man in the shadow breaths: “The Latinian Embassy is under observation, Herr Loder. I await your signal.”

At first the bemused guests indulge in small talk, which suggests that each is already acquainted with the other.

On entering the large white marble room, the Ambassador’s wife makes an immediate beeline for Loder who assumes that he, a lowly journalist, has been invited to such a prestigious gathering merely because he’s once frequented in the same club as her and her husband. Carla dismisses this theory, reminding Loder that he is in fact the owner of eighteen magazines and eleven newspapers; his influence on society might in fact be greater than that of any of the other guests. “On the contrary,” he replies. “In a democracy, newspapers don’t control anything. We merely inform.”

Above Right: Peter as Werner Loder on stage

Meanwhile on the opposite side of the room, von Schiltz, Fessel and Markheim have formed a huddle to and discuss the possible reason for this mysterious invitation – each quietly pondering both his and the others possible role. All agree that Loder is indeed the most unwelcome of dining partners, since previous encounters with the publishing magnate has resulted in a damaging exposes for each of them.

As the gusts sip champagne and ready themselves for dinner, a white van draws up outside the Embassy, and from it a wheelchair carrying an elderly man is unloaded by a tall, blond youth. A camera lens peeps through the broken window of the warehouse in an attempt to identify the passengers. Without uttering a word, the two men are directed inside the Embassy building.

Amidst the political banter, the Ambassador’s attention is drawn to an insistent light that flashes and send s him rushing to the door. After checking his wristwatch, he demands the attention of his powerful guests, and announces the arrival of a most important individual.

With his face almost entirely obscured by a woollen scarf, the person in question is pushed into the room by the tall blond youth, where they’re met with a deathly silence. The Ambassador begs the patience of the mystified gathering, who begin joking amongst themselves – comparing the evening’s entertainment to a game of charades.

As the youth slowly begins to remove the layers of wrapping from around the face of the old man’s face, the assembly reel in disbelief and horror at the startlingly familiar features that are revealed to them. After the gasps have subsided, the old man is ushered from the room, and it’s left to von Schiltz to utter just a single word: “Alive!”

Below: A cutting from the Times-Herald: Friday, April 12th, 1963.

With catlike curiosity, Werner Loder pounces on the Ambassador to confirm what they have all just seen: “Adolf Hitler! But how…?” The Ambassador explains that, just hours before Germany fell to the Allies in 1945, Hitler had been flown out of Berlin by the Luftwaffe, and had been given refuge in Iceland. It was there that he’d lived in a safe house just outside of Reykjavik. He now felt that it was time that he faced his accusers, and the men present at the Embassy had been handpicked to act as judge and jury.

Of all of them, Fessel appears the most agitated by the events of this most strange of evenings. Whilst the others all demand confirmation from the man himself, Fessel remains tight lipped , and appears relieved when the Ambassador suggests that, for the moment, only general von Schiltz should be allowed to speak with him.

Having deduced that the old man is now incapable of speech, Loder enquires how they might be expected to communicate with him. Loder is informed that the youth – Hitler’s son, Adam – is to speak on his behalf. But as Loder points out, Adolf Hitler was known to have been impotent, and would’ve therefore be unable to father a son. “His impotence appears to have been slightly exaggerated”, quips Carla. “Like his death!” adds Loder, extinguishing a cigarette.

Adam’s re-entry to the room goes unnoticed as the gathering debate who amongst them will take part in the “trial”, and who will abstain. The Ambassador explains the Hitler is content to let his fate rest in their hands.

Before deliberations even begin, both von Schiltz and von Markheim demand that the old man must be executed there and then. Loder, however, has a more practical solution: Why not exhibit him in a zoo: “Behind bars, of course!”

Loder asks von Markheim why he might wish to see of The Fuhrer so quickly: might it have something to do with the reopening of old wounds? After all, was he not among those that financed Hitler’s rise to power in the first place!

Although the Archbishop agrees in theory with the General and the Shipbuilder, he feels that he cannot condone any bloodshed. Loder suggests proposes that von Markheim’s past record must disqualify him from sharing his opinion. Fessel, on the other hand, refuses outright to discuss and alternative, which would most certainly result in the German government handing Hitler over to the Israeli authorities for the extermination of 6,000,000 Jews.

Loder submits that it’s the right of the new German to deal with the old, – saying that, unlike his powerful companions, he did not lie for Hitler, nor did he build ships or pray for him.

Von Markheim implies that Loder’s argument is based entirely on the question of age, to which the journalist relies: “Is it my age that you can’t forgive, von Markheim? What you can’t forgive is that I didn’t share in your legacy; a legacy of guilt! You won’t rest until every single German helps you carry that intolerable load. But we won’t share that with you, von Markheim, not any of us. The guilt is on your back, and there it will remain!”

Although he acknowledges his own guilt, von Markheim claims that he was merely a victim of the time; he was given order, and he obeyed them. For that, he says, he was thrown into prison to ease Germany’s conscience. Fessel agrees, but insists that this isn’t the time for private quarrels: regardless of the views of the individual, Adolf Hitler must be tried, found guilt and hanged!

In an attempt to bring order to the assembly, the Archbishop proposed that, whatever the outcome, their decision must be forever kept within the confines of the Embassy walls, lest each man present that evening might one day himself be unpleasantly compromised. He goes on to curse the Ambassador for placing them in such an intolerable position.

Von Schiltz thoughts, it appears, are somewhat less cloudy. He professes that, because of Hitler, the good name of the Germany Army had been tainted by the worst atrocities known to mankind, and as far as he was concerned, the old man must be disposed of. “Dispense with your butchery if you must,” he comments, “but not with my blessing!”

Werner Loder immediately reminds Himmermann that he was not quite so sparing when he himself sent out the man of the SS to commit THEIR atrocities. “Forgive them, “mocks the pressman, between mouthfuls of bread and paté, “for they know not what they do!”

Von Markheim concludes that, should they take the Archbishops advice, they themselves might be accused of attempting to spare Hitler’s life. In their own interests at least, the General should have his way.

Karl-Hines Fessel now finds himself with the casting vote, but without a moment’s hesitation, agrees with the majority – but only with the assurance that the evenings events should never be made known to the public via the newspapers.

“But aren’t you forgetting something?”, interrupts Loder. “What about Adam?” Whatever would stop him coming forward at some point in the future to tell of his father’s private execution? Then, he admits, it would be his duty to publish the story.

At that very moment, Adam enters the room to thank each man in turn on his father’s behalf:

To Franz von Markheim, he gives thanks for fending off all attempts to break up his empire, and for retaining much of the Fatherland’s wealth.

To General Otto von Schiltz, he gives his highest commendation for rehabilitating Germany’s Armed Forces for the historic mission of defending the free world.

To Karl-Hines Fessel, he offers gratitude for upholding the ideal of the greater Germany, and to Archbishop Himmermann, he offers thanks for absolving the German people of all feelings of guilt for their past.

But what of Wener Loder? A salute for enlightening the people to the corruption upheld in the so-called democratic way of life.

With that, the old man is once again wheeled into the room to face his ‘judges’. “You have made your decision/”, Adam enquires, coldly. “Eh, no!”, replies von Markheim. “Tell your father we need more time.”

Once again the debate rages, but this time only Werner Loder insist that Hitler must be destroyed, whilst the other attempt to excusing The Fuhrer’s existence by justifying their own. What would each individual gain by sparing the old man’s life?

The abolition of a free press, perhaps? The complete destruction of all political opposition? And, of course, the rehabilitation of the Armed Forces and the freedom to re-arm? In the adjoining room, Adam and his father listen intently to the arguments and grin inanely.

As a nearby clock tower announces the arrival of dawn, von Schiltz declares that a final decision must be reached. At the request of Karl-Hines Fessel, the General is invited to assume power in the name of the German government, which he readily accepts for the greater good of the “Fatherland”.“

“Excellent!”, Fessel declares. “From tomorrow, we shall argue from a position of strength!”

Raising his hand in an attempt to demand reason, the Archbishop observes that Fessel is already speaking with “his” voice. But already the plans are being drawn for the rebirth of the German state, and with von Markheim in full support, the three men request an audience with their Fuhrer.

But what of Werner Loder? An offer of complete control of the nations press, and the opportunity to exclusively report plans for the “new Germany”.

…”Or?” Arrest and execution!

Left: Peter as Werner Loder in the television adaptation of the play

On refusing their terms, Loder reveals that he’s taken precautions in the form of the man at the warehouse window, who awaits his signal. Determined that no such signal will be given, von Schiltz draws his pistol and fires a single shot that rips through Loder’s left shoulder, sending him withering to the cold marble floor.

Directly, the General gives orders for his men to deal with the spy in the warehouse – telling Loder that his colleagues death rests firmly on his shoulders.

A telephone call is made results in orders being given for the deployment of armed troops to defend Germany’s eastern boarder against possible Communist reprisals, and a toast is made to the Fatherland.

And from his wheelchair in the doorway, his son standing proudly at his side, the all too familiar voice of Adolf Hitler explodes into the room…

“We will not fail. The men and women of Germany will dedicate their lives to the restoration of the Reich, which will last a thousand years. We will not fail. God is with us!”

Werner Loder looks on with horror!

In Retrospect

‘Night Conspirators’ by former theatre critic, Robert Muller, was characterised at the time of its premier as “The most exciting thriller to have been written in recent years”. His subject was hugely fascinating and while not entirely new, it was treated with a perception and an accuracy that was, to say the least, disturbing.

The play sported a formidable line-up of familiar names whose inclusion bore out the high hopes expected of Muller’s work. What it was about had to remain a secret because the dramatic impact of the first act depended very much on surprise.

Suffice it to say that it was one of those “possibilities” which, like the Loch Ness monster, the audience could savour all the more satisfactorily as long as it’s neither proved nor disproved. This particular monster is proved but still managed to retain an intriguing air of unreality.

Having thereby rather restricted any detailed analysis it was only possible to continue with generation. Muller reached into a bag of dramatic devises and pulled out a plumb of considerable size, not in the pure theatrical sense but in the intensely personal reactions of his plot. He set out to investigate truth with some unpleasant situations; he dug into ego and false pride and split them; and he found that guilt, hypocrisy and blind devotion are incorrectable parts of a man’s character. The full implications of the play’s theme were followed up ruthlessly.

The story was written with tension as the key-word, not the contrived tension of a second-rate whodunit but compelling, mounting tension which relied equally on dialogue and stage technique. Occasionally an odd cliché jarred slightly but these were few enough to be excusable.

Critics Comment

“From Peter Wyngarde there is a triumphant portrayal of a truth-seeking newspaper publisher”. Time Herald – Friday, 12th April, 1963

Note of interest

A Professor of History commented: “The author of ‘Night Conspirators’, Robert Muller, – himself a German refugee who fled to England in 1938 – imagined a fugitive Führer conspiring with post-war German elites to create a Fourth Reich as means of casting doubt in the political reliability of the Federal Republic.

‘Night Conspirators’ was significant, finally, for the considerable attention it attracted. In Britain the play met with a largely positive reception. Muller’s pessimism about post-war Germany’s structural continuities with the Nazi’s past resonated with British viewers – many of whom agreed with the drama’s skeptical assessment of the nation. One wrote that his work provided “A terrifying and all too likely glimpse of the future”.

Not unsurprisingly ‘Night Conspirators’ met with an angry response from the Germans. Indeed, the West German Ambassador to Britain went so far as to protest to the airing of the television drama and declared his hope “That a play like this will never again be shown on British television”.

From ‘The World Hitler Never Made: Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism (New Studies in European History). Cambridge University Press. Gavriel D. Rosenfeld, 2005.

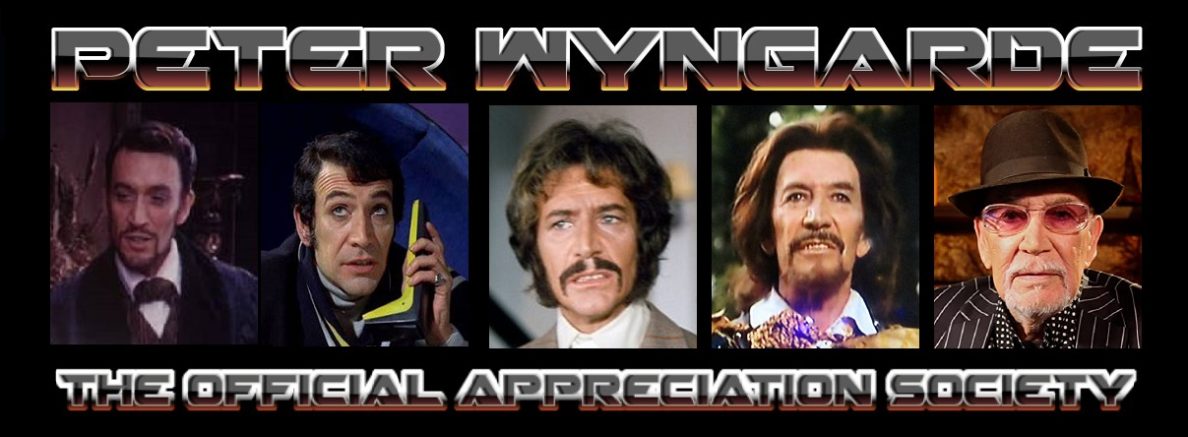

© Copyright The Hellfire Club: The OFFICIAL PETER WYNGARDE Appreciation Society: https://www.facebook.com/groups/813997125389790/

2 thoughts on “REVIEW: Night Conspirators”