| We lay my love and I beneath the weeping willow. But now alone I lie and weep beside the tree. Singing ‘Oh willow waly’ by that tree that weeps with me. Singing ‘Oh willow waly’ ’till my lover return to me. We lay my love and I beneath the weeping willow. A broken heart have I. Oh willow I die, oh willow I die. |

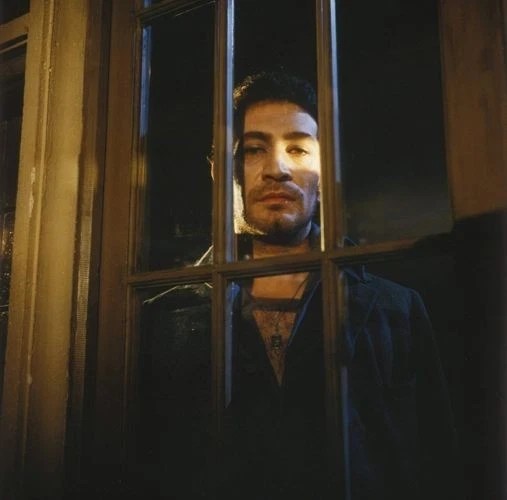

Peter as Peter Quint

The Story

‘The Turn of the Screw’ is one of the great ghost stories in world literature, Henry James’ 1898 novella, It has been adapted countless times for the stage, television, cinema and even as a ballet, an opera (by Benjamin Britten in 1954) and a graphic novel (by Guido Crepax in 1989). Among the many film versions, however, most agree that The Innocents (1961), directed by Jack Clayton, is the most elegant, evocative and frightening of them all.

Below left: Original costume design for Peter Quint

The screenplay by Truman Capote was actually based on the 1950 stage adaptation by William Archibald and may be one reason Henry James purists find fault with the 1961 film version. The story of a governess, Miss Giddens, who is entrusted with the care of two small children, Flora and Miles, by their uncle at a remote country estate, James’ novella creates a mood of dread and menace through the increasing anxiety of Miss Giddens who suspects that the children may be influenced and corrupted by the malevolent spirits of the deceased former governess, Miss Jessel, and caretaker Peter Quint of Bly House. The beauty of The Turn of the Screw is that you are never sure whether Miss Giddens is imaging the supernatural occurrences or whether they are actually happening. In The Innocents, there is never any doubt that Bly House is haunted – you see the ghosts. Yet a sense of mystery and ambivalence still exists regarding the children. Are they conduits for the evil spirits or truly innocent? Miss Giddens’ obsession with discovering the truth brings a feverish intensity to the proceedings which are almost as chilling as the phantoms she seeks to exorcise.

In Conversations with Capote, conducted by Lawrence Grobel, the author recalled his involvement on The Innocents: “When it was offered to me to do it as a film, I said yes instantly, without rereading it…Then I let several weeks go by before I reread it and then I got the shock of my life. Because Henry James had pulled a fantastic trick in this book: it doesn’t stand up anywhere. It has no plot! He’s just pretending this and this and that. It was like the little Dutch boy with his fingers trying to keep the water from flooding out – I kept building up more plot, more characters, more scenes. In the entire book there were only two scenes performable.”

Regardless of Capote’s comments about Henry James’ novella, he based the screenplay structure on the Archibald stage adaptation and added the Freudian subtext of Miss Giddens’ repressed sexuality which surfaces in scenes of a disturbing erotic nature such as an uncomfortably long goodnight kiss between Miles and his governess. Playwright and screenwriter John Mortimer (Rumpole of the Bailey) is also credited with adding additional scenes and dialogue for The Innocents.

In the biography Deborah Kerr by Eric Braun, director Jack Clayton recalled how The Innocents and the casting of Deborah Kerr as Miss Giddens came about. “Deborah had one film to do for Twentieth Century [Fox], and so did I: that was the one we both wanted to do and which we had discussed when we met the previous year. I had admired her work in two films with that very underrated actor, Robert Mitchum – Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison [1957], which showed her at her best without makeup, and The Sundowners [1960], in which her freckles were so attractively in evidence.”

Kerr remarked in the same biography on her performance: “I played it as if she were perfectly sane – whatever Jack wanted was fine; in my own mind, and following Henry James’ writing in the original story, she was completely sane, but, because in my case the woman was younger and physically attractive – Flora Robson had played her wonderfully on the stage – it was quite possible that she was deeply frustrated, and it added another dimension that the whole thing could have been nurtured in her own imagination.”

Filmed on Locations in East Sussex, England and Shepperton Studios in Surrey, The Innocents proved to be a physically challenging role for Kerr. Clayton said, “To achieve what we wanted in the monochrome photography the arcs had to be of considerable intensity, and the atmosphere on the set, with fifteen “brutes” burning away, often stifling. During a long schedule, imprisoned in those voluminous Victorian dresses, she never complained, never showed a trace of the discomfort she had been feeling.” She also had to do a scene that required numerous retakes where she had to carry Martin Stephens (who was cast as Miles) in her arms. She later revealed to the director that she had felt quite ill and feverish during that day of filming but never acknowledged it at the time.

Clayton discovered prior to production on The Innocents that the film needed to be shot in Cinemascope, a screen format he did not want to use. Luckily, he had one of the best cinematographers in the business working for him – Freddie Francis; they had previously collaborated on Room at the Top (1959). In The Horror People by John Brosnan, the cameraman recalled that, “…I had quite a lot of freedom, and I was able to influence the style of The Innocents. We worked out all sorts of things before the picture started, including special filters. I still think it was the best photography I’ve ever done – as much as I like Sons and Lovers [1960] I think The Innocents was better, but you rarely get an Academy Award for a film that isn’t successful no matter how good your work on it.”

Left: A rare still taken during filming. Peter is seen standing on a platform to the far left.

As strange as it seems now, The Innocents didn’t receive any Oscar® nominations. It did garner international awards such as a Best British Film nod from the BAFTA and a Palme d’Or nomination at the Cannes Film Festival. Still, the film was not a box office success in the U.S. Francis said, “I’m sure Jack [Clayton] was terribly disappointed with the reaction that The Innocents received. He, unfortunately, gets terribly tied up in his films. Everybody, I’m sure, involved with it thought it was a great picture and I’m not completely sure what went wrong but I think it was because it was based on Henry James. When you read James you’ve got to think about it and make up your own mind…The film lacked this ambiguity and I think, basically, that was the reason it wasn’t a success…in the film all the suspicion fell on the children – whereas having read The Turn of the Screw one doesn’t know whether it is the governess who is a bit strange or the children.”

Deborah Kerr has her own theory about why The Innocents wasn’t a success at the time. In the Braun biography, she noted “The subtlety with which he [Clayton] and his team established the atmosphere of the two worlds – the everyday and the spirit world – was so evocative of decadence, in the most delicate manner, that it completely escaped the majority of the critics. Today, a new generation of young movie “buffs” realise how extraordinary were the effects he achieved. One instance is the way the edges of the screen were just slightly out of focus, as though seen through a glass, perhaps. Now it is acclaimed as a great work of art; then they didn’t push it because they didn’t know how to respond to something so genuinely spooky – so interwoven with reality that it could be real – and that’s something people didn’t like.”

Not all of the critics unfavourably compared The Innocents to Henry James’s original novella. Pauline Kael of The New Yorker called the film “one of the most elegantly beautiful ghost movies ever made…The filmmakers concentrate on the virtuoso possibilities in the material, and the beauty of the images raises our terror to a higher plane than the simple fears of most ghost stories. There are great sequences (like one in a schoolroom) that work on the viewer’s imagination and remain teasingly ambiguous.”

Besides Clayton’s superb direction, Francis’s stunning cinematography and Kerr’s masterful performance (possibly the best of her entire career), The Innocents is distinguished by an unforgettable supporting cast including Michael Redgrave in a brief opening cameo, Megs Jenkins as the fretful Mrs. Grose, Peter in a chilling, non-speaking role as Quint, Clytie Jessop, equally silent but haunting as Miss Jessel and two of the finest child actors of their generation – Martin Stephens as Miles and Pamela Franklin as Flora. Stephens had already made a strong impression as the blonde alien child leader in Village of the Damned (1960) but he would retire from acting in 1966 and pursue an education in architecture. Franklin would go on to star in other similar genre efforts such as The Nanny (1965), And Soon the Darkness (1970), Necromancy (1972), The Legend of Hell House (1973) and The Food of the Gods (1976).

Among the other notable adaptations of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw are numerous television productions including a 1959 version with Ingrid Bergman (directed by John Frankenheimer), one in 1974 with Lynn Redgrave (directed by Dan Curtis), one in 1995 entitled The Haunting of Helen Walker with Valerie Bertinelli, Michael Gough and Diana Rigg, and one in 1999 with Jodhi May and Colin Firth. Film versions of the novella include the 1985 Spanish film Otra vuelta de tuerca, directed by Eloy de la Iglesia (Cannibal Man, 1973), The Turn of the Screw (1992) with Patsy Kensit, Stephane Audran, and Julian Sands, Presence of Mind (1999) with Sadie Frost, In a Dark Place (2006) with Leelee Sobieski, and even a prequel to the events in the James story entitled The Nightcomers (1971), a kinky S&M portrayal of Quint and Miss Jessel played by Marlon Brando and Stephanie Beacham. None of them appear to have the fervent cult following of The Innocents which looks better and better with each passing year.

| The Innocents: Forbidden Games By Maitland McDonagh – 2014 It is Quint’s ghost that shakes Miss Giddens’s optimism to the core, and casting Peter Wyngarde, a TV actor with a handful of minor movie credits, as the serpent in Bly’s tranquil garden was an underappreciated stroke of brilliance. Little-known in the U.S. but a familiar face on UK television, he was born to the part. Quint is never seen to do anything overtly indecent—in fact, he’s never seen to do anything more than peer in windows, walk along a rooftop, and allow himself to be glimpsed in a mirror. The spirit of his disgraced lover is merely sad, but his rudely sensual physicality—especially disturbing in a ghost—is palpably malignant, and it’s clear that Quint’s greatest offence was not just possessing but embracing the kind of coarsely potent maleness that drives the natural world but is abhorred by a particularly refined notion of civilization, one that defines and is defined by the story’s women. |

Awards & Nominations

1961

- National Board of Review, USA

- Awarded (NBR Award): Best Director – Jack Clayton

1962

BAFTA

- Awarded: Best Film from any Source

- Nominated: Best British Film

Cannes Film Festival

- Nominated (Palme d’Or): Jack Clayton

Directors Guild of America

- Nominated: Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures

- Awarded (DGA Award): Jack Clayton

Edgar Allan Poe Awards

- Awarded: Best Motion Picture

- Best Script: Truman Capote and William Archbald

Writers Guild of America

- Nominated: Best Written American Drama: Truman Capote and William Archbald

- In 2014, The Innocents was voted ‘The Most Frightening British Horror Film Ever Made’ by the British Film Institute.

MILE’S LAMENT TO PETER QUINT

| “What shall I sing to my lord from my window? What shall I sing, for my lord will not stay? What shall I sing, for my lord will not listen? Where shall I go, for my lord is away? Who shall I love when the moon is arisen? Gone is my lord, and the grave is his prison. What shall I say when my lord comes a calling? What shall I say when he knocks on my door? What shall I say when his feet enter softly, leaving the marks of his grave on my floor? Enter my lord, come from your prison. Come from your grave, for the moon has arisen!” |

Critics Comments

| There are few moments in cinema as primally scary as Peter Wyngarde’s gliding ghoul appearing at the window. The Guardian One of the most elegantly beautiful ghost movies ever made. The New Yorker A ravishing neo-romantic takedown of Victorian repression, spooky and scathing in equal measure. The AV Club The Innocents manipulates the viewer’s imagination as few films can, with Kerr and Redgrave doing a masterful job of creating a sense of repressed hysteria. TV Guide Magazine A perfectly balanced adaptation of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, with Deborah Kerr in her greatest performance. The Seattle Times The film thrives on unsettling images of overgrowth and rot, such as the dead flower that drops at Kerr’s touch, and the beetle that crawls obscenely out of the mouth of a cherub statue. The Telegraph One of the scariest films ever made. Deborah Kerr gives one of her greatest performances as a rather high-strung governess. The Los Angeles Times Catches an eerie, spine-chilling mood right at the start and never lets up on its grim, evil theme. Director Jack Clayton makes full use of camera angles, sharp cutting, shadows, ghost effects and a sinister soundtrack. Variety Director Jack (Room at the Top) Clayton, sensitively seconded by Cameraman Freddie Frances, has filled every coign and corridor with a dangerous, intelligent darkness. Moreover, the main performances are most capably carried off. Time |

Sound of Cinema: Landmarks – The Innocents

A Landmark edition recorded in front of an audience at the British Film Institute as part of the Sound of Cinema season: Matthew Sweet is joined by the film’s stars Peter Wyngarde and Clytie Jessop, psychoanalyst Susie Orbach, writer and critic Christopher Frayling and stage and screenwriter Jeremy Dyson to examine the British horror classic The Innocents.

Images: (Above Left) – Matthew Sweet and Peter. (Below Right) – Peter, Susie Orbach, Clytie Jessop & Jeremy Dyson.

The Innocents is a supernatural horror film based on the novella The Turn of the Screw by Henry James starring Deborah Kerr as Miss Giddens, the young governess who begins her first assignment caring for two orphaned children on a remote estate. She becomes convinced that the house and grounds are haunted – the film achieving its gothic effects through lighting, music and direction rather than conventional shocks, as we follow the increasingly erratic behaviour and visible deterioration of the ever-present governess. But are we watching a real ghost story or is this just the projection of the imagination of the repressed governess?

As part of Radio 3’s Sound of Cinema season, Matthew Sweet and guests are joined by an audience at the British Film Institute for a Landmark edition of Night Waves, to examine how the combination of cinematography, the script of William Archibald and Truman Capote and Georges Auric’s original music and the direction of Jack Clayton created a masterpiece that terrified even the critics.

Producer: Laura Thomas.

Credits

Presenter: Matthew Sweet

Guests:

- Peter Wyngarde

- Susie Orbach

- Christopher Frayling

- Jeremy Dyson

- Clytie Jessop

Featured in…

- Landmarks A series from Free Thinking and Night Waves devoted to celebrating cultural landmarks.

- Sound of Cinema season Listen to highlights from the Sound of Cinema season on Radio 3.

The Innocents voted one of the Top 10 most scary films of all time by The Guardian

This is absolute classic British black-and-white horror, creepy and atmospheric despite – or perhaps because of – the elegance and gentility of its visuals. Adapted fairly freely from Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, via William Archibald’s play and Truman Capote’s dialogue, it was directed by Jack Clayton, who had just had a big hit with the kitchen-sink flagwaver, Room at the Top. The Innocents couldn’t be more different.

Essentially, it is a story of possession. Deborah Kerr plays Miss Giddens, a governess hired to look after little Flora and Miles by their uncle (Michael Redgrave). The pair initially seem sweet and fun but, as is the way with creepy horror-film kids, they soon turn demonic and troubled. The first intimation of this arrives when it transpires that Miles has been expelled from school, as a “bad influence”; this is compounded by the children’s odd behaviour, apparent secrets and reports of strange visions.

Miss Giddens eventually connects all this to two previous employees of the house, both dead: governess Miss Jessel (Clytie Jessop), and valet Peter Quint (Peter Wyngarde), who were locked in an abusive relationship. Are Jessel and Quint using the children as vehicles to continue it from beyond the grave?

With legendary cameraman Freddie Francis on board, supplying arguably his most spectacular visual accompaniment to the action, this is a film in which setting and atmosphere play a significant role in beefing up the Freudian subtexts. The final scene earned the film an X-certificate on its initial release, and an enduring reputation as a properly disturbing depiction of repressed sexuality.

Above Left: Peter as the ghost of Peter Quint atop ‘Bly House’ and, Right, the house at Sheffield Park, East Sussex, where the scene was shot.

Click below for more information on ‘The Innocents’…

2 thoughts on “REVIEW: The Innocents”