Presented by Stephen Michell Theatre Productions Ltd. at the Theatre Royal, Brighton – March 1968 and at The Duke of York’s Theatre, London – May 1968.

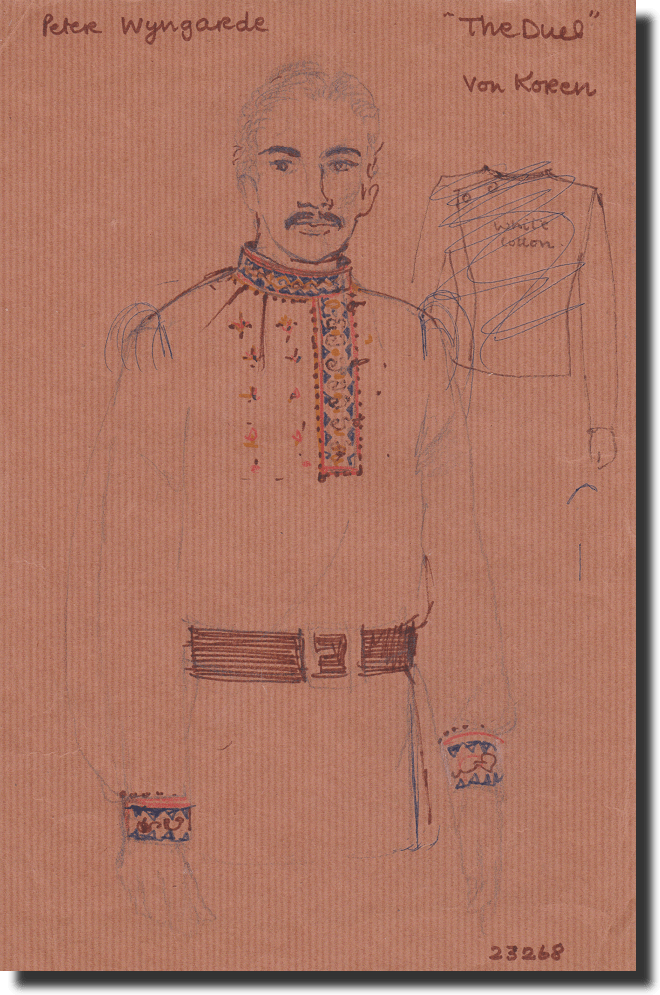

Character: Nicolay Von Koren.

The Story

The action takes place in the house of Alex Samoylenko and André Laevsky at a resort on the Caucasian Coast of the Black Sea, in the Autumn of 1891.

Anton Chekov didn’t pen many plays, although those he did write became extremely popular on Forties and Fifties radio, and in the Sixties on television. All did remarkably well – perhaps because these were the mediums that the author would’ve used at the time of writing if they’d been available to him. Short stories are often themselves well suited to forms of restraint. Director and adaptors, it would seem, were drawn to Chekov’s work because of the apparent ease in which the playwright could make an otherwise inert situation glow with interest.

When it came to the theatre, however, it was a different matter. Unoriginal as it may be to say so, if Chekhov had wanted his (longer) short story, ‘The Duel’, to have been a play, he’d surely have written a play. And this production showcased at the Duke of York’s by an Iowan PhD, Jack Holton Dell, whilst a capable job, makes it all the clearer that Chekhov was right.

Right: Peter as Von Koren

In the open scenes the typically Chekhovian characters and ingredients are all there – at least on the surface. A gauze backdrop representing a heaving stretch of the Black Sea coast rises to reveal a proverbial summer residence; its windows and doors thrown open to catch the breeze.

We now find ourselves in a Caucasian resort in the long hot summer of 1891. Here, in a sleepy and specific moment of time, where the cross-currents of lives which had been gently slumbering are about to be awoken.

There’s Alex Samoylenko (James Hayter) – a laid-back and welcoming ex-military physician, played by James Hayter; Marya Konstentine (Elspeth March), a hectoring and tightly-corseted matron, her husband and daughter, Katya (Janet Hannington), plus the self-important officer, Igor Kirilin (John J. Carney), who fancies his chances with the young lady.

In addition, we have Atchmianov (Anthony Watkins) – a draper, and Pobyedov (Lewis Fiander), an likable virginal deacon. Also into this provincial backwater, the author throws in three interlopers: André Laevsky (Michael Bryant) – a liberal arts graduate, who is pining for his hometown of Moscow and Nadya Federovna (Nyree Dawn Porter) – whom he’s been involved with for several years. And as if for good measure, there’s Nickolay Von Koren (Peter Wyngarde) – a German Marine Biologist with Nietzschean-Nazi ideals about the future of the race, and who has spent the summer on the Black Sea studying the development of the jelly fish.

Below (from left to right): Peter, James Hayter as Alex Samoylenko and Lewis Liander as Deacon Pobyedov.

Naydya, it occurs, is a married woman – only her husband is dead, tho’ her lover hasn’t got around to telling her yet. The two have been on the run for two years, and now as he reaches a high point of frustration with the affair, she takes other lovers and run up a series of debts at Atchmianov’s shop. Together the two have caused a public scandal by “fornicating” in the Black Sea waters.

Thunder rumbles occasionally off stage, which signifies that we’re at the wonderfully clear point of time before the storm breaks. The play’s theme tangles around love and violence as a means to an end. It’s a affecting essay in human foolishness and objectives; in other words, what is probable and what is possible. Expressed in those generous yet mildly scornful terms in which Chekhov saw his fellow man, it made appealing viewing.

The play produced so many unswerving similarities with the immediate past. For instance, isn’t it our own society – distressed and dazed by its own freedoms, disgusted at its own liberalism – that is correspondingly keen to find a Nicolay Von Korden within its number? This campaigning botanist, preaching his scientific tyranny; haven’t we heard his deadly logic before – pre-1939? Don’t some, even good liberal souls such as Deacon Pobyedov here, flirt dangerously with its persuasive strength as a welcome relief from all the indecisiveness and gloom around us now?

The splendour, of course, flows from the Chekhov essence of the piece – a flavour faithfully re-created by the author and given the understated quietness of portentously repressive emotion by director, Norman Marshall. I got a feeling of a mood preserved moments before it crumbled to dust; like an autumn leaf caught in full beauty just before its irreversible decay.

In Retrospect

It never ceases to amaze me how many of Anton Chekhov’s unhurried 19th Century reflections find their echo in the commotion of the present day. Watching his expressive creations eat out their hearts and act out their predicaments on stage takes on an almost self-absorbed fascination, like watching our modern condition reflected in a stylishly gilt, but slightly grubby mirror.

I must admit, though, to a complete and inexcusable ignorance of the Chekhov novel on which Jack Holton Dell had based ‘The Duel’. Consequently, with all the fewer trees with which to see the wood, I was able to judge it on the theatrical entity in itself. No side-tracking round to check whether or not the author had remained true to the original. And as a play, it hit me as a thing of unique splendour and arresting significance.

(Left): An original poster from the Duke of York’s Theatre.

Only hours before I saw a recording of this play, I’d watched some archive film footage from the Seventies and one hitherto rational fellow human being uttered the statement: “Student demonstrators! They ought to shoot a few. That would stop all the violence!” The speaker doubtless imagined himself as deeply rooted on the side of law and order as Nickolay Von Koren does when he speaks out so fervently and convincingly against the freedom of individuals to follow their individuality. His damnation of André Laevsky and Nadya Federovna for their chaotic emotions was a tremendous feat of twisted truths.

Peter made out of it a towering piece of theatre, as he did with the whole role. It was little wonder watching his handsome menace, that Laevsky, the object of his fervent hate, says: “Tomorrow the world will be run by men like him; and we will be the ones who put him in power.”

There were, however, a number of questions and puzzlements with which I was left. For instance: after the Deacon has illustrated the virtues of light through love, Von Koren on his world of superior men, and Madam Konstantine on the dangers of moral corruption, there is an abusive argument between Laevsky and Von Koran, but no apparent reason is given for the subsequent duel, during which Laevsky is shot in the neck. All we get is a blackout! That’s it.

We’re told that Laevsky and Nadya are to be married. Why? Has the Deacon, who had been seen as a religious buffoon, now become a considerable spiritual authority? Had the bullet from Von Koren’s pistol, perchance, softened Laevsky’s brain? Or might the scientists’ assault on his character compelled him, shuddering and quaking, into the obsessional arms of Nadya? He is, we’re invited to believe, a changed man, but are provided no real reason why.

Perhaps Chekhov’s translation is clearer in the original story, but it was most certainly a serious flaw in the play.

Press Article

The Sunday Times: 5th May, 1968

| Jack Tinker at the World Premier AN AUTUMN LEAF IN FULL BEAUTY It never ceases to intrigue me how many of Anton Chekhov’s languid 19th century musings find the echo in the clamour of our present day. Watching his eloquent creations eat out their hearts and act out dirt dilemma’s onstage takes on an almost narcissistic fascination, like watching our modern malaise reflected in an elegantly gilded slightly dusty mirror. I must, however, confess a total and lamentable ignorance of the Chekhov novel on which Jack Holton Dell as based the play that had its world premiere at Brighton’s Theatre Royal last night. Thus, with all the fewer trees through which to see the wood, I can judge it only as a theatrical entity in itself. No side tracking round the proscenium to check whether or not the author remains faithful to his original. And as a play it strikes me as a thing of unmistakable beauty and striking relevance. The beauty, of course, flows from the Chekhov flavour of the piece, a flavour faithfully recreated by the author and giving the supple stillness of ominously oppressive heat by director Norman Marshall. One gets that feeling of a mood crystallised it before it crumbles to dust; an autumn leaf caught in full beauty just before the point of irrevocable decay. Thunder rumbles occasionally off stage. We are at the magnificently clear point of time before the storm breaks. The play’s theme angles around love and violence as means to an end. It is a poignant essay in human folly and human aspiration; what is probable and what is possible. Couched in those generous yet gently mocking terms in which Chekhov saw his fellow creatures, it makes irresistible viewing. So many direct parallels with the immediate present and the immediate past. For instance, isn’t our own society – alarmed and shaken at its own freedoms, sitting at its own permissiveness – equally willing to find a Von Koran in its midst? This crusading botanist preaching is scientific tyranny; haven’t we heard this poisonous logic before pre-1939? Don’t some – even good liberals souls such as Deacon Popyedov here – flirt dangerously with its persuasive strength as a welcome relief from all the indecision and greatness of purpose around us now? Only hours before I took my seat in the theatre, I had listened to one hitherto rational fellow human being uttered the sentiment: “Student demonstrators! They ought to shoot a few. That would stop all the violence!” The speaker probably imagined himself as deeply entrenched on the side of law and order as Von Koran does when he speaks out so passionately and persuasively against the freedom of individuals to follow their individuality. His damnation of the play’s tortured lovers for their anarchy of emotion in a tremendous feet of twisted truths. Peter Wyngarde makes out of it a towering piece of theatre, as he does with the whole role. Small wonder, watching his handsome menace, that Andre Laevsky, the object of Von Koran’s passionate loathing, should say: “Tomorrow the world will be run by men like him; and we will be the ones who put him in power.” Michael Bryant, as Laevsky, gives the line a weary, saddened emphasis as though to heighten its inevitability; the comparisons are too obvious to list. More to the play’s point; doesn’t blood still spill before men of opposing ideals find themselves shaking hands? All through this sensitively felt production there are performances which have their own delights. Lewis Flander as the earnest, innocent young deacon delving breathlessly to find sweetness and light in every dark corner; James Hayter as the portly military doctor beaming a benign commonsense; Bruce Walker, neatly dodging the overwhelming hypocrisy so splendidly perpetrated by Elspeth March, with the quiet dignity of a husband not yet henpecked out of existence. For Nyree Dawn Porter’s glamorous golden Nadya the can be nothing but glorious golden praise. Here, if ever there was, is woman teetering on the brink of her own ruin, poised on the rim of eternal sadness in the pursuit of lasting happiness. You know a compelling disturbing piece of theatre. |

Associated Items

Peter in his dressing room at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London. The photograph was taken by James Hayter (who played Alex Samoyenko in ‘The Duel) and is signed and dedicated by him on the back. It was here that Peter was first introduced to Joel Fabiani – his future ‘Department S’ co-star.

Original sketches of Peter’s costume in (left) Pen & Ink and, (right), watercolour.

Above: Peter’s copy of the script showing amendments and additions in his own hand.

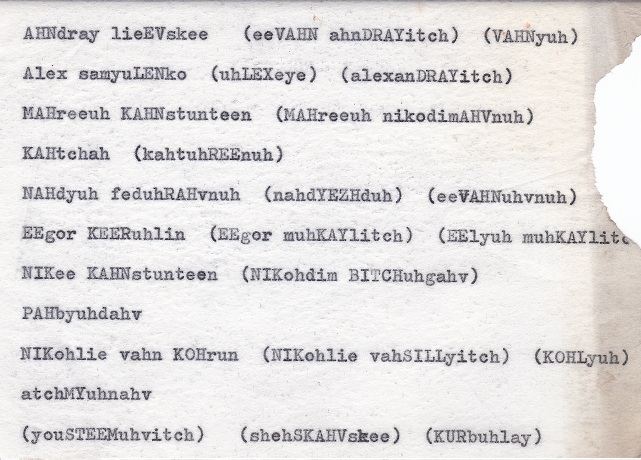

Above: This is a copy of an supplementary sheet that was added to Peter’s script to help with the pronunciation of certain Russian names and words.

Above: Full page (broadsheet) advertisement for the play in the 5th May 1968 edition of The Sunday Times.

2 thoughts on “REVIEW: The Duel”