Please note that some of the additional information provided here by the journalist named below may not be accurate, so it should be treated with caution.

29 May-4 June, 1971

The Peter Pan World of Peter Wyngarde

The Man Without A Past

15 years ago, Peter Wyngarde played Sydney Carton in a TV production of A Tale of Two Cities. He received 2,500 fan letters, one of them from a woman who replaced a Van Gogh from over her fireplace with his photograph.

It is interesting to see, in retrospect, in the curious prudishness of the Fifties, Wyngarde became a heartthrob by playing the past, while today, after a solid middle-of-the-order TV career in which “heavy” and “typical bastard” parts abound, he has emerged a heartthrob once more – playing the present. You can’t, after all, have anything more ‘now’ than Jason King: ask the 35,000 women that mobbed him in Sydney, Australia.

To look at Wyngarde as he was – playing Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew, or flicking a deft sword in Cyrano de Bergerac (his first big stage success), or receiving rave notices in London’s West End and on Broadway in Duel of Angels with Vivien Leigh – and to look at him now, you almost see two different men.

Then he looked like any continental actor (he is Anglo-French), his hair tightly waved, cropped short, and his teeth bared in a lover’s smile or a swine’s sneer, dominating his face.

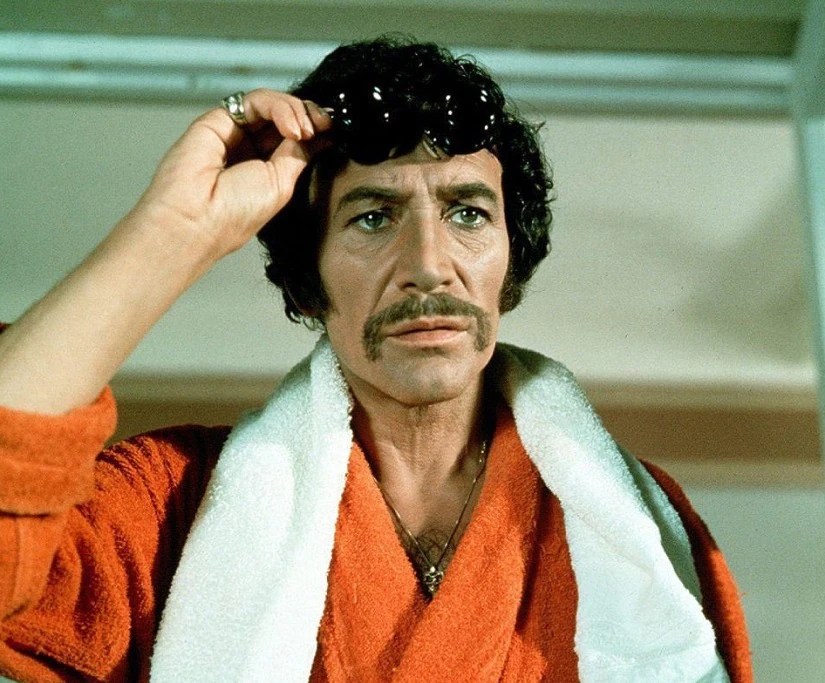

Now Wyngarde looks like no one but himself, unless you want to be cruel and see a likeness to gypsy guitarist Manitas de Plata. The hair, greying quickly, rings the face like an Edwardian libertine’s and the teeth have become secondary to the droopy moustache.

Time has made the face thinner, the nose more equine and deeply sculptured the flesh beneath the eyes. Time may not be cruel but it is inexorable. It’s passing, however, bothers Wyngarde not a jot: he has had to live to get a face that way. Not that he’ll talk about his past. He has no Proustian compunction to remember it, at least not in public: and he never strays beyond those areas he has already clearly defined and bartered for publicly in the journalists marketplace.

“I don’t believe in the past,” he told me with simple abruptness when we met for lunch in one of London’s most “in” restaurants. “I never think of it unless people force me into it. I prefer to be a man without a past, and my entire philosophy is based on that. The present is what interests me. I’m really just beginning to live now. That man of 15 years ago certainly has nothing to do with me. Each phase of my life has been left and is now dead. The kernel stays the same, put the development must be allowed to extend. I feel, if anything, that I have had to mature very slowly, not only now am I at the stage where most men are in the early 20s. Imagine someone in their early teens and comparing that with what he is in his early 20s, and you may grasp why I am such a different person from the man I was”.

The man is father to the boy and the boy Wyngarde has been extensively written about. At the age of 12, when Shangai fell to the Japanese, he was captured in the Chinese town of Lung-Hau (his diplomat father was away on a mission) and had left him with friends and was put into a concentration camp. He was there for four years and was tortured by rifle butts on the bare feet for carrying messages between huts. It took two years in a Swiss sanatorium for him to recover from malaria, malnutrition and his injuries. The major clues to the man is buried there.

“It might sound odd, but although I went through hell at that camp, I was barely aware of it at the time,” Wyngarde said. “It was only in later years that I realised just how bad it must have been. My young mind flapped down and shut out a lot of it. That is something to do with my desire not to remember the past. Not just that, but any period. Perhaps I’ve overdone it and I now apply it even to the good things. But that’s it. That’s why I think I matured slowly. I wasn’t just deprived of much of my childhood, I lost a lot of my adolescence, too. If you take that vital stage away from a person’s development then the whole process of becoming a man is vigorously distorted. I almost feel that I am having my adolescence now. No doubt about it. But I don’t think it has anything to do with being a television star. It would have been the same if I’d been in any kind of job. In many ways it’s much more fun than having your adolescence when you’re in your physical teens. For instance, I can talk to young people well, marvellously. All my real friends are very young. And I’m always in the company of young people. To tell you the truth, when I’m with an older person I nearly always feel about 18. More often than not, I feel very shy, too. One night I was at a private dinner were there were some very important people, all wealthy and getting on a bit. Throughout the whole evening I felt like the young son of the household being allowed in for his first adult dinner”.

Television has a way of making Wyngarde look like a small boy, physically. In fact, he’s well-built, if lean, and a little over middle height. What kind of a person he was as a young man it is difficult to hazard: he was in his mid-20s when the newspapers and magazines began to pick him up in the late 50s, and then they were more interested in his two cars and his breakfast habits and his fencing practise in the garage than him. Perhaps that was only he allowed them to be interested in. Wyngarde, in any case, refuses to be led into any area of his past which might give away his age, an attitude which can only partly be explained by his repugnance for the past. The little boy again?

One has much greater sympathy with his refusal to discuss marriage, other than in the abstract. He was married, he says: it lasted five years and that’s the end of it. To whom he was married and when, is nobody’s business but his own. Different sources have him married at ages varying from 22 to 38. “It’s the past,” he shrugged, refusing to be drawn. “It’s over there somewhere. Would I get married now? I don’t want to get hurt again”. And then he added, the small boy given way to Jason King which tends to happen when Wyngarde is under pressure, “Life is too short to spend with one woman”.

If he refuses to turn his head to look behind him, Wyngarde is eager-eyed for the future – the future which becomes the present before rushing into the past. What of Wyngarde’s future?

“I must do movies,” he said, “and not just because of whatever money might be in it, either. Put it like this, we live through our ears and through our eyes. Now, in this simplest form, the theatre is sound, spoken word. And by comparison, in its simplest form, film is sight. I have come to realise that my natural creativity is a visual one. That’s why I want to make films. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not knocking television. It is a magnificent medium for a visual actor. But with television I am not all that fond of the basic principle of using four cameras. I think that in a way that’s like doing a painting with four painters. One painter with one brush stroke can give greater simplicity. To me, films are all about economy along with an ability to experiment to a greater degree. The whole trend nowadays is to create character. Now the only thing that gives character to a modern audience is action. Just to put someone there to mouth words is no longer good enough. There must be action, too. Moving pictures defined themselves. I believe that in that special sphere lies the best means of satisfying my need for self-expression”.

At the moment, Wyngarde is having fun (he’s fond of that word) and he’s making the most of it. He has the tax bills to prove it. On that subject: “I love living in London and I hope I won’t be forced to leave purely for tax reasons. Actors spend many years struggling and then only a few make it into good money. We bring a fortune into the country and I do think the whole tax thing should be reappraised, don’t you?”

And Wyngarde, one time hopeful in advertising and the law (he tried writing too) and self-confessed fantasist, smiled… a small boy smiling from a lived-in face.

Interview by T.C. Rhode.

One thought on “INTERVIEW: TV Times”