Let battle commence!

Over the years as Secretary of The Official Peter Wyngarde Appreciation Society, I’ve received many a strange, interesting and controversial letter from fans (and foes!), but not provoked such a reaction from our membership than the following, which was written by Mr Paul McGuinness of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne.

| Dear Tina, I remember that it was around 7.30 in the evening when ‘Department S’ first appeared, but being just a child, I felt that it was just like ‘The Champions’, which had just finished its run. However, it was not long before I was into the storyline – hook, line and sinker. I remember vividly that the first episode was ‘The Ghost of Mary Burnham’. I also recall the announcer at the end saying it wasn’t the episode scheduled to be shown. It helped that the first episode to be shown was such a good one, as they clearly wanted to show the best stories first to get people interested. I think that the reason ‘Department S’ was so big was because of the blatant commercialism. This had a lot to do with Edwin Astley – composer and arranger. Another reason was the scripts. They were excellent – they were strong and the lines were straight and to the point. The acting was great too, but this is where everyone is wrong in not recognising the other members of the cast, who were less flamboyant than Peter Wyngarde, but who gave the show a base. ‘Department S’ was NOT Peter Wyngarde; it was a combination of all the things I’ve mentioned above. I can only think that in 1970, Peter Wyngarde was God (well, he thought so!) People told him that it was HIS performance that made the show, disregarding his fellow actors in the series, who were not recognised or given credit by the media, or through the public. If ‘Department S’ was the most blatantly commercial show of all time, the ‘Jason King’ was just the opposite. Geoffrey Howe one destroyed the economy with one budget. I expect Peter Wyngarde destroyed his career with 26 episodes of ‘Jason King’! The scripts were dreadful. There was no Joel Fabiani or Rosemary Nicols to give the show balance. His image was changed from a masculine one to a rather thinner version of Frank Spencer. maybe subconsciously he wanted to destroy the character. He certainly destroyed him in the eyes of the public. Yet there is no doubt that this man can act. His performance in ‘The Saint’ episode, ‘The Man Who Likes Lions’ will verify this. ‘The Saint’ sometimes suffered because many episodes were just the same, but in this episode he was a rather masculine one where he got his role from within and is probably a truer expression of himself. This is why he appealed to so many women. This is why I want to come back to ‘Jason King’, because it was this series that destroyed the credibility of Peter Wyngarde. He will never be forgiven! Patrick McGoohan, who I recently watched in a Sunday night film, fell into the same trap when he left ‘Danger Man and did ‘The Prisoner’, which was complete rubbish, and he never recovered! There’s little doubt that ‘‘Department S’’ was the best detective series ever made. Today, they make programmes for two hours which introduce characters. In my opinion, two hours is too long. You need to be direct with the scripts. The music has to be exciting, bring the show to its thrilling climax, and keeping its audience on the edge of their seats. I would very much like to know if Peter was given the chance to do another series of ‘Department S’, and if so, did he turn it down? Did he get on with the other members of the cast, and does he regret making ‘Jason King’? Also, do you know if Rosemary Nicols wore a wig in the show, or was she advised to do so, as she looks so much better? Was Anthony Nicholls from ‘The Champions’ her father? Paul McGuinness |

It was clear based on the questions at the end of this letter that its author was more than a little confused as to who – or more specifically, WHAT he was writing to. The clue to our concern was in the title: The Official Peter Wyngarde Appreciation Society. We were not a club specifically devoted to ‘Department S’, therefore the enquiries relating to Rosemary Nicols were somewhat misplaced [1].

Nevertheless, I welcomed Mr McGuiness’s contribution as I’ve done all others, and

respected his opinion, although I myself didn’t completely agree with it.

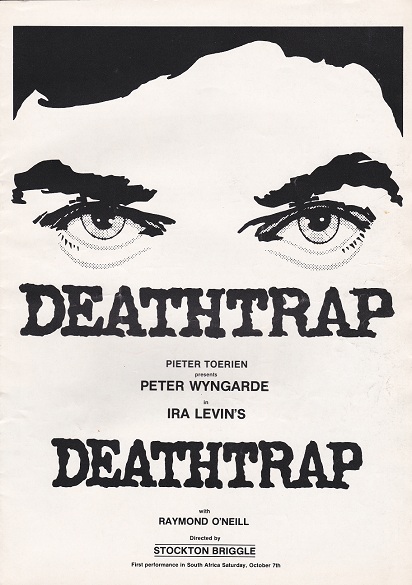

To begin with, Peter’s move from ‘Department S’ to ‘Jason King’ in 1971, wasn’t his choice but that of Lew Grade and ITC. He certainly had no influence over the fate of the characters – Annabelle Hurst, Stewart Sullivan or Sir Curtis Seretse. And whilst Mr McGuinness clearly doesn’t rate ‘Jason King’ as highly as he does the original series, his opinion is just that: a mere view-point – not fact. There are many fans who actually prefer ‘Jason King’ to ‘Department S’ – one of those people being none other than ITC’s own Dennis Spooner [2].

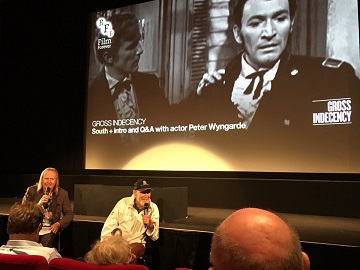

Another fallacy that was touched upon in McGuinness’s letter is that Peter’s career was somehow “destroyed” post ‘Jason King’. This point has been discussed several times in other articles in this Blog, so I won’t go through it all again. What I will say, however, is that it’s clear that most people see Peter solely as a television actor, and that when he chose to return to the stage after he completed the final episode of ‘Jason King’, certain members of the public simply believed he’d disappeared.

Mr McGuinness’s lack of awareness concerning Peter’s post-‘Jason King’ career is one thing, but as a self-confessed fanatic of a show which he declared as “the best detective series ever made”, you’d have at least expected him to know that ‘The Ghost of Mary Burnham’ was not the first episode o ‘Department S’ to be shown on British TV. The debut episode was, in fact ‘Six Days’, which was broadcast on Sunday, 9th March, 1969. ‘The Ghost of Mary Burnham’ was actually shown much later on Thursday, 18th February, 1970.

Following my reply to Mr McGuinness, a number of fans decided to join the debate. These included the following:

“Mr. McGuinness definitely lost me when he wrote that ‘The Prisoner’ was “complete rubbish”, said Uwe Sommerlad. But he’s got a (single) point – ‘Department S’ was a better show, as far as I’m concerned, and it had to do with the balance; having just Jason King gave us the pleasure of seeing more of Peter Wyngarde, but it became a tad too fanciful. ‘Jason King’ needed a down-to-earth element it lacked – a Watson to Sherlock Holmes (“You are the one fixed point in a changing world, Watson.”), you may say, to make sure it’s only a 7% Solution and not an overdose. “Having said that – Jason King is still a very entertaining show, of course. And who needs the (fine) Edwin Astley when he gets the (great) Laurie Johnson?”

Wayne Webster added his thought as follows: ‘In ‘Department S’, l like the chemistry between Peter Wyngarde and Joel Fabiani who were great together. The Jason King character was perfect for the time. As for the Jason King series the more l revisit the series the more l like it (l know some think this series was not strong). Peter Wyngarde should be proud of this character.”

‘It might be fair to say the three leads on ‘Department S’ are like a balanced meal – starter, main, and dessert. Jason king is just dessert – and while that is my favourite course it is best not to over indulge”, Hellfire Club member, Patrick Nash said .

“However, this letter seems to be from someone craving attention and sadly he is getting it. ‘Danger Man’ is just about forgotten today – ‘The Prisoner’ considered a classic of all time. ‘Department S’ is

just about forgotten – Jason king fondly remembered. While it would be interesting to hear Peter Wyngarde’s views on how ‘Jason king’ affected his career it has to be said it has granted him a sort of immortality – and that is due to the solo show. It seems many other people also have a fondness for dessert.”

Diane Brierley, meanwhile, says that she’s a fan of both series: “Peter was brilliant as Jason King in both series. I can’t think of a single other actor who could have given life to this sexy, flamboyant character the way Peter did. The first time I watched him in ‘Department S’ he had me hook, line and sinker! Personally I have to say that I preferred the story lines in ‘Department S’ but it was always Peter’s show. Joel was fab too but I think Annabelle could have been played by any actress. Rosemary never came across as very special in the part to me. Just to add, ‘Department S’ absolutely WAS Peter Wyngarde for without his acting ability, superb voice and diction and ability to make Jason King the primary character the programme would not have been the success that it was. Not forgetting his damn good looks and style obviously!!”

“Well, everyone is entitled to their opinion,” Australian, Tania Donald says pragmatically. “TV shows and movies are such a matter of personal taste after all – but I wouldn’t think that these views outlined above are held by many of Peter Wyngarde’s admirers. ‘Department S’ and ‘Jason King’ are different shows, by design. I think it would have been very evident to the producers of ‘Department S’ that Peter was a huge part of the show’s success and the next logical step would be to cater to the public’s admiration of Peter by showcasing his talents in his own series – which Jason King did and very successfully too. Peter is amazing in Jason King and the shows huge and continued popularity says much more about his masterful performance than the personal opinion of one fan ever could’.

‘Both shows are fabulous. Each shows different sides to the character, with the series Jason King being a more personal portrayal. The fact that nearly 50 years later we are here discussing this should be testament enough to the quality of Peter‘s performance!’ Dave Asher.

‘I always loved ‘Department S’ because it seemed to have lots of sci-fi and weird bits to it. Jason King, on the other hand, my mum used the like (I wonder why?) but as a youngster I could never get into the stories and it was on quite late at night as well.’ David James Manning.

After the above comments were posted on our Facebook page, I then received the following email from Jeannette Griffiths from Perth, Australia:

| Dear Tina, I’m not usually much of a letter writer, but after reading Paul McGuinness’ manic utterings I felt compelled to put pen to paper. Although I accept that most people associate Peter with Jason King as, without doubt, the flamboyant author was his most popular and best-loved creation to date, it really makes my blood boil to think that there are still such narrow-minded people out there who seem to think that that once ‘Jason King’ came to an end in 1973, Sir Lew Grade stuck Peter in a box and put him up in the attic with the Christmas tree and old photo albums! In spite of your selfless hard work in bringing the countless aspect of Peter’s extensive career to our attention, it still hasn’t sunk in with certain cloth-heads out there that the character of Jason King was not, and never will be, the pinnacle of Peter Wyngarde’s career. If Paul McGuinness had been paying attention, he’d have noticed how often Peter has stated in interviews that, just after ‘Jason King’ ended its run on TV, he had no desire to make another long-running television series, and only wanted to return to the theatre – which I believe he did with great success. Surely it doesn’t take an Oxford don to work out that actors don’t just drop off the face of the earth the moment we switch of out TV sets! Had it not occurred to Mr McGuinness that, perhaps, Peter saw himself primarily as a stage actor and that, maybe, ‘Department S’ and ‘Jason King’ were merely a diversion from what he saw as his main vocation? What some people clearly fail to understand is that television isn’t the be all and end all of a professional actors life. In fact, many thespians still look down on the box as the ‘Poor Relation’, and frown upon those who make it their life’s work. Based on the reviews I’ve read, Peter’s career actually hit a peak after ‘Jason King’ finished, and did not nosedive as McGuinness advocates. My advice to those people who think that Peter’s career amounts to nothing more than a four year period between 1969 and 1973, is to get off the couch, potato brain, and grab a life! |

I also received this missal from Mr Grayson Dunning from Mid Glamorgan, who reacted thusly:

| Dear Tina, I’m writing in response to Paul McGuinness’ letter. Whilst I disagree with some of what he says, he’s not as wide of the mark as some people might think. There are three points in his letter that I’d like to make. Firstly, I do believe that Joel Fabiani played an important anchor role in ‘Department S’ and was a vital to its artistic, if not commercial, success. His down-to-earth and fact-seeking character kept the drama grounded in realism as Jason went off on his flights of fancy. But let’s not be mistaken, it was Peter who gave the show its colour and impetus; he supplied its adrenalin, if you like, and it was he who the viewers tuned in to watch. As for Rosemary Nicols, the less said about her the better! (How could she have possibly have believed herself to be an actress of any real worth with THAT voice?! Every time I hear it I’m reminded of the scene in ‘Jaws’ where Robert Shaw scrapes his fingernails down a blackboard!). Secondly, looking from a fundamentalist viewpoint, dramatically and intellectually, ‘Jason King’ is inferior to ‘Department S’. However, it is not “rubbish”; to anyone like myself who has a deep love of all things Wyngardian, and who can happily sit through fifty minutes of Peter free-wheeling through all manner of ludicrous mayhem; coiffured and tarted up like a prize peacock, then its manna from heaven. therein lies its underrated appeal. On a pure ‘fun’ scale, it outstrips ‘Department S’. Thirdly, I agree with Paul: ‘Jason King’ did ruin Peter’s TV career. But I think one can go even deeper to the core of the problem than Paul did in his letter. The more I think about it, and without being too harsh, it was Peter’s own fault. The character of Jason King became too over the top and cartoonish in its depiction of the ‘ideal woman’s man’. And Peter made the fatal mistake of allowing the boundaries between actor and character to become blurred you can see this in the countless interviews given at the time). he fell for the sex symbol status he acquired and encouraged it, instead of distancing himself; keeping his head down and making people sit up and concentrate of him as an actor (as opposed to wondering what he might be like in the sack!). Peter seemed to revel in his pin-up status but it doesn’t do your career any good over the long term. People forget you’re an actor, and stop taking you seriously as one. You become a caricature, as Peter did – linked to a particular era of TV. But, inevitably, in TV as in everything else, when one era eventually comes to an end another one begins and some of the baggage is left behind – often the most defining people of the previous era, because they’ve become old fashioned; unhip, or inextricably linked to a bygone age: an anachronism. Only in recent years has Peter become revered by fans of all things cult. The general TV audience has a shallow appreciation of what’s put in front of them, with a limited attention span, which the TV producers are in tune with and respond to. Unfortunately, to the general television audience Peter was, and always will be Jason King from the Seventies; ‘medallion man’. If only he hadn’t allowed character and actor to merge into one all those years ago, who knows what else he might’ve achieved on TV. On the other hand, Peter’s theatrical career thrived because the stage is a completely different animal; it draws in a limited yet more cultured audience that would have a deeper appreciation and understanding of Peter’s work. After all, there is no doubting he is one of the finest, most talented actors of his or any generation. I wonder if he actually now feels that he allowed himself to get too closely linked to the Jason King character at the time, or whether he had a preference for either ‘Department S’ or ‘Jason King? Well let’s find out… |

It was then Peter’s turn to weigh into the debate…

| Dear Grayson, I’d just like to say that I couldn’t agree with you more about Joel’s contribution to ‘Department S’ but, as usual, money raised its ugly head and the producers would only make the second series (‘Jason King’) if they had just one wage bill alone to pay and not three ! (The tailor’s bill alone was more than my salary!). Secondly, I don’t think that ‘Jason King’ was in anyway inferior to ‘Department S’ – just different. I do think, however, that the lack of finance was partly responsible for the absence of good locations etc. In the first series, Jason was only brought in at the very last moment when all else had failed. In ‘Jason King’, the idea was to discover a more ‘private self’; a deeper and more serious side to the character. Looking back now, perhaps he should never have been exposed to all those other influences, or allowed to take himself so seriously. Unfortunately at times, sentiment became more important than the plot. I do feel it was a mistake to make Jason so vulnerable, and in retrospect, that was perhaps the only major fault of the series. However, on a fun scale, it did outstrip ‘Department S’. Now to a very important point: Acting is about being the person you play., and I think an actor succeeds only if he becomes the character he portrays – totally, which is what film and television acting is all about. Alas, it appears that it’s been a faithful audience which has blurred the imagery in this case. Finally, I think that you’ve got the point of one era ending and another beginning slightly out of focus, and that the “baggage” to which you refer has itself become the dumping ground as opposed to the era itself. After all, that “era” has once again come around, the difference being that now some people prefer to call it ‘Cult’. You must remember that ‘Jason King’ was a send-up of the James Bond films of that time, and this was the point of its humour. As you know, Bond won all his fight whilst Jason, on the other hand, rarely ever emerged unscathed from his! Like the master once said: “There is too much nonsense spoken about sex as there is too much nonsense spoken about television!” After all, they’re both primarily there to entertain; a talent to amuse. Sincerely, Peter P.S. And can we please stop referring to Jason King as a “Medallion Man”! After all, the only time he ever wore a medallion was when he went undercover as another character, in the ‘Shake & Shout’ scene in ‘The Man From X’ (‘Department S’). |

What are your thoughts on the Department S v Jason King debate; which series don prefer? Let us know here!

[1]. I pointed Mr McGuinness in the direction of the Actors Equity to see if they might be able to assist him in contacting Ms Rosemary Nicols, or her representative.

[2]. Story Consultant on both ‘Department S’ and ‘Jason King’.

© The Hellfire Club: The OFFICIAL PETER WYNGARDE Appreciation Society: https://www.facebook.com/groups/813997125389790/

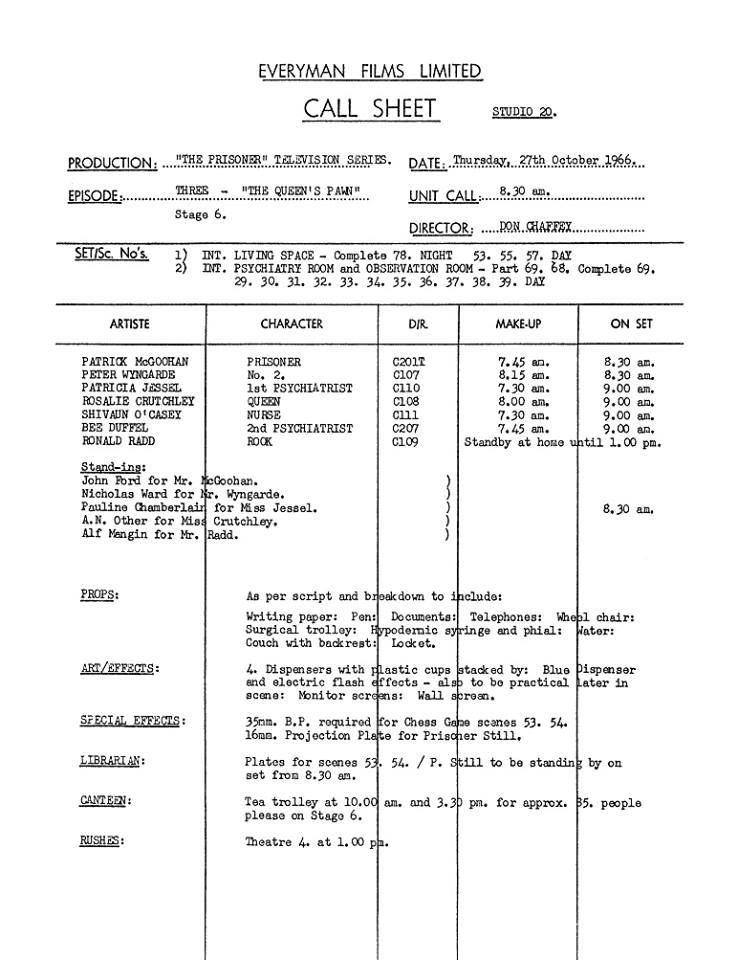

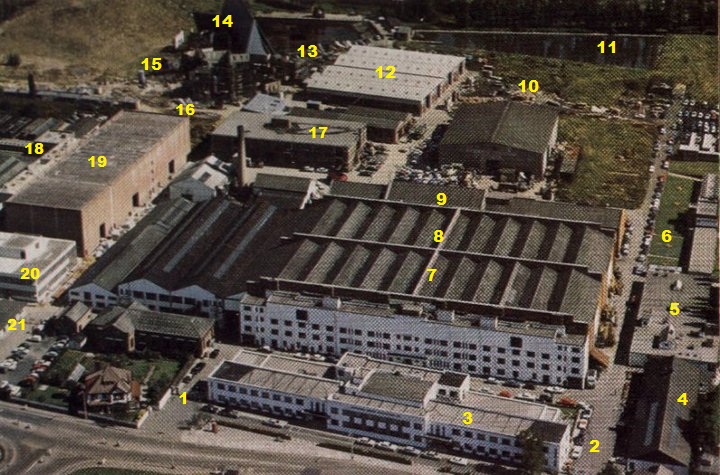

the third screen and the fourth screen. So there was always a tiny bit of technical hitch going on there; there was always a bit of hold-up while they did those sorts of things. Waiting for the thing to do – it was a bit like watching a television, or a video now where you go (imitates a voice running backwards) it all goes back and you’ve got everybody going like that, and you come back on it. So there was a lot of technical things to do. I remember a fight that I had on a platform while these things were going on and I suddenly thought – we all stopped, because we thought ‘Oh my God! It means that every time we throw a punch we’ve got to match it up with the thing over there!’So Patrick very sensibly shot it at a different angle so we didn’t have to do all that. He was very good, you know, as a director. He should’ve directed a great deal more, I think.

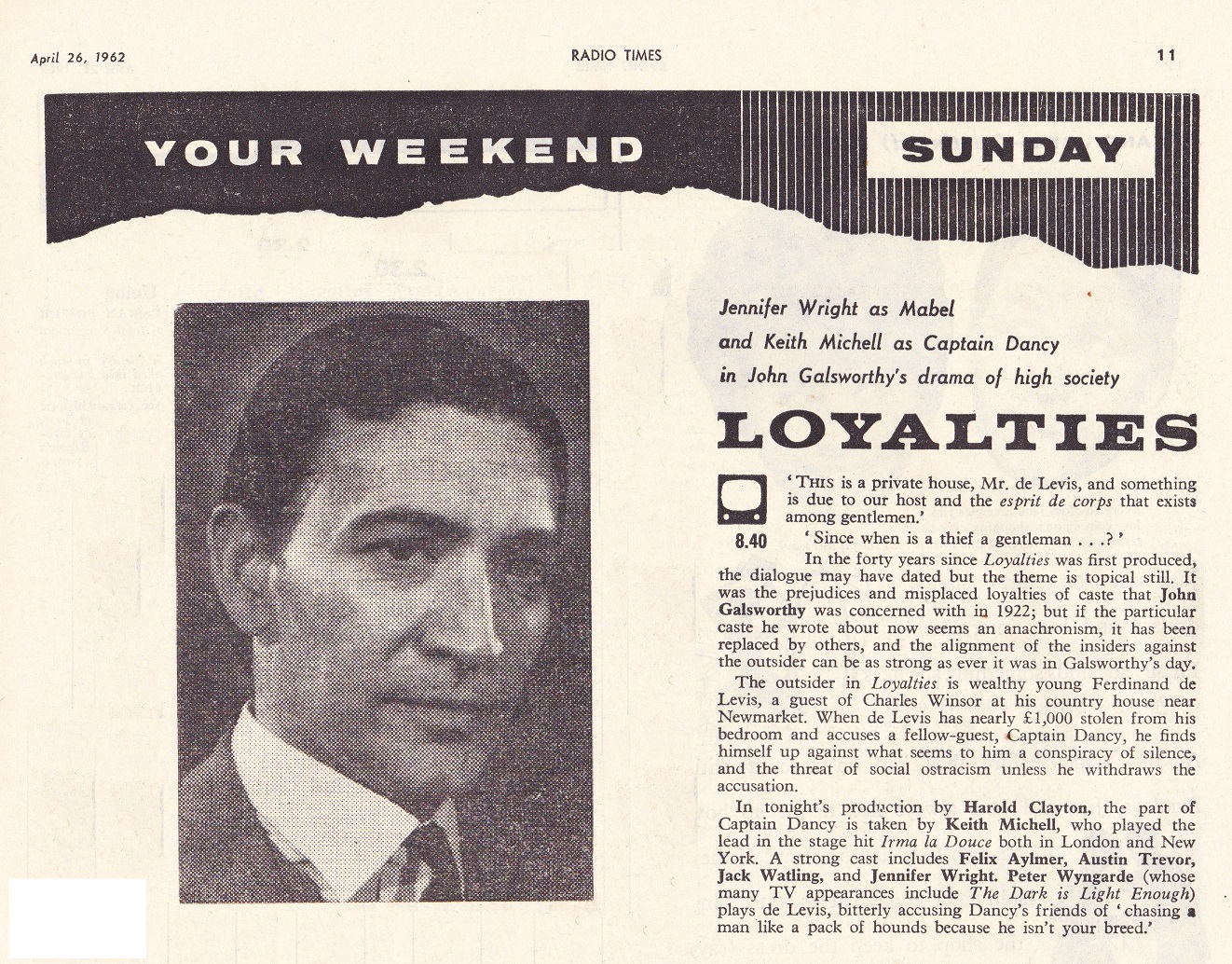

the third screen and the fourth screen. So there was always a tiny bit of technical hitch going on there; there was always a bit of hold-up while they did those sorts of things. Waiting for the thing to do – it was a bit like watching a television, or a video now where you go (imitates a voice running backwards) it all goes back and you’ve got everybody going like that, and you come back on it. So there was a lot of technical things to do. I remember a fight that I had on a platform while these things were going on and I suddenly thought – we all stopped, because we thought ‘Oh my God! It means that every time we throw a punch we’ve got to match it up with the thing over there!’So Patrick very sensibly shot it at a different angle so we didn’t have to do all that. He was very good, you know, as a director. He should’ve directed a great deal more, I think. You remember, you said you thought that I had shot some of the ‘Jason King’ thing over here at the Thatched Barn; I don’t think we did. I think we shot ‘The Saint’ (The Man Who Liked Lions) here. I have a feeling. I remember an orgy scene by a pool (laughs), and we were all supposed to dress up in Roman costumes. That was the time that Roger (Moore) and I were supposed to fence at the end of it, or sword fight – not fence. A sword fight. I pretended to Roger that I’d never picked up a sword in my life, and that I didn’t know what to do. In fact, I’d fenced at the Green Club (London) – you know, the whole thing – and I love it, absolutely love it. So I thought it would be a little game with Roger, and we had to do this fight thing, you see, and every time he came along to see how the doubles were doing with me, I would go: “Oh! Oh! Oh, God!” And I said: “Roger, do you think it would be better if you did it with a double?” He said: “Peter, we must see your face!” “So,” I said, “Can’t we just do it like they do in the Errol Flynn movies, you know, and have my face looking fierce like that?” He said: “Come on, have a go! We have one big take, OK?” It was ‘The Man Who Liked Lions’, that’s what it was called, and I had to knock him – bang, bang, bang, bang, and he gets hold of me and sticks the sword in me, and I fall into the lion’s den, which is the end of the movie – marvellous big moment. So he said to the stunt boys: “He’s a bit tricky about the fighting, isn’t he? Never mind, I’ll make him look tough; don’t worry. Then we can do the cuts and that sort of thing”. So I just went and really let him have it. And I went bang, bang, bang, bang, and I got Roger. He fell into the lion’s den! That was the episode that was filmed here.

You remember, you said you thought that I had shot some of the ‘Jason King’ thing over here at the Thatched Barn; I don’t think we did. I think we shot ‘The Saint’ (The Man Who Liked Lions) here. I have a feeling. I remember an orgy scene by a pool (laughs), and we were all supposed to dress up in Roman costumes. That was the time that Roger (Moore) and I were supposed to fence at the end of it, or sword fight – not fence. A sword fight. I pretended to Roger that I’d never picked up a sword in my life, and that I didn’t know what to do. In fact, I’d fenced at the Green Club (London) – you know, the whole thing – and I love it, absolutely love it. So I thought it would be a little game with Roger, and we had to do this fight thing, you see, and every time he came along to see how the doubles were doing with me, I would go: “Oh! Oh! Oh, God!” And I said: “Roger, do you think it would be better if you did it with a double?” He said: “Peter, we must see your face!” “So,” I said, “Can’t we just do it like they do in the Errol Flynn movies, you know, and have my face looking fierce like that?” He said: “Come on, have a go! We have one big take, OK?” It was ‘The Man Who Liked Lions’, that’s what it was called, and I had to knock him – bang, bang, bang, bang, and he gets hold of me and sticks the sword in me, and I fall into the lion’s den, which is the end of the movie – marvellous big moment. So he said to the stunt boys: “He’s a bit tricky about the fighting, isn’t he? Never mind, I’ll make him look tough; don’t worry. Then we can do the cuts and that sort of thing”. So I just went and really let him have it. And I went bang, bang, bang, bang, and I got Roger. He fell into the lion’s den! That was the episode that was filmed here.