Presented by the English Stage Company at the Theatre Royal, Brighton and the Royal Court Theatre in London. October 1956.

Character: Yang-Sun

The Story

The play takes place in the Chinese town of Setzuan in the 1930’s

- Prologue: A street, evening

- Scene 1 – A Small Tobacco Shop

- Scene 2 – Wang’s Sewer Pipe by the river

- Scene 3 – The Tobacco Shop

- Scene 4 – The Municipal Park

- Scene 5 – Wang’s Sewer Pipe

- Scene 6 – The Tobacco Shop

INTERVAL

- Scene 7 – The Tobacco Shop

- Scene 8 – A Private Dining Room in a cheap restaurant

- Scene 9 – Wang’s Sewer Pipe

- Scene 10 – The Yard behind Shen Te’s Shop

- Scene 11 – Shaui Ta’s Tobacco Factory

INTERVAL

- Scene 12 – The Tobacco Shop now an office

- Scene 13 – Wang’s Sewer Pipe

- Scene 14 – A Courtroom

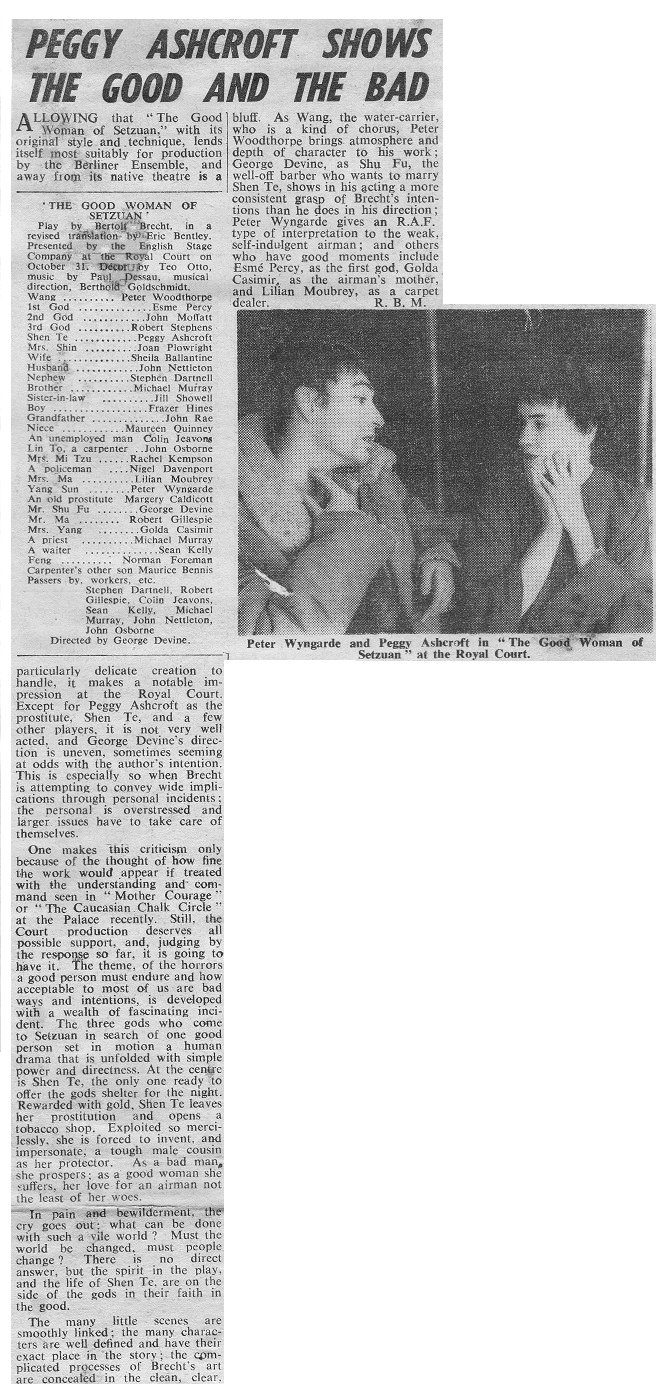

Peter as Yang-Sun – an unemployed pilot

| “…as Shen Ta, she falls in love with a worthless airman; at least, he is worthless to most people, only Shen Te, through her love, seeing in him potential nobility.” Raymond Marriott – Plays and Players, December 1956 |

Producer George Devine was surely carrying out his obligations to the audience he had created at the Royal Court Theatre in attempting the first ever professional full-scale production of Bertold Brecht’s play in English. The difficulties were formidable: his stage wasn’t big enough to begin with; nor, in fact, was his resources. The comparatively small number of actors he was able to afford were not, naturally, trained in the kind of acting that Brecht demanded – indeed, some were even expected to take on more than one part. However, the attempt proved well worth making and, even if the difficulties were not fully overcome in this production, the effort was a courageous one and deficiencies were more than compensated for by the performance of Peter Wyngarde, who tackled the difficult role of the good-for-nothing Chinese airman, Yang Sun, both imaginatively and professionally.

The little fable on which the three-hour play was strung is very simple (and none the worse for that!). Three Chinese deities – played by Esme Percy, John Moffatt and Robert Stephens – set out from Heaven on a quest. The world is to be destroyed unless they can find one good man or woman in it. For a time not only are they unable to find a good person – they don’t even meet a bad person with enough enlightened self-interest to pretend to be good! However, just when all appears to be lost, the three gods happen upon the small village of Setzuan, where a poor prostitute by the name of Shen Te takes them in thinking them to be beggars, and offers them food and shelter.

To reward her kindness, the gods give her a bag of gold with which she buys a tobacconists shop, and she is at last able to escape both her old profession and her poverty. As with so many prostitutes in fiction, Shen Te (Peggy Ashcroft) has a heart of gold, and as might be expected, some of her less scrupulous neighbours seize upon the opportunity to take advantage of her good nature, preying on her hospitality and eating her out of house and home.

At last she is forced to invent a tough male cousin, Shui Ta (herself in disguise) who, with the help of a policeman, drives the rabble from the shop. As herself, she falls in love with Yang Sun (Peter Wyngarde), an unemployed pilot and promises to find him the large bribe necessary to buy himself into a job. However, as her male cousin and protector, she discovers that the airman is only using her for his own ends, but by now she has not only been betrayed and exploited, but is pregnant by him too!

Nevertheless, as the tough ruthless male, she flourishes, and after setting up a tobacco factory, installs the pilot as her foreman who, by grinding down the poor, makes a fortune for his employer. Wickedness, it appears, is always rewarded whilst goodness is trampled upon.

Below: Peter’s own sketch of his character, Yang Sun

Knowing that Shen Te has a stake in her cousin’s thriving business, Yang Sun accepts her proposal of marriage, and a wedding party is arranged to take place at the tobacco factory. But when the pilot discovers that his intended bride knows of his deception, he attempts suicide. In spite of his dishonesty, Shen Te takes pity on the weak, self-indulgent airman when she finds him about to hang himself in the woods. Sitting under a tree in the rain, she diverts him with a charmingly told ‘Story Of The Cranes’.

During the coming weeks, She is forced more and more frequently to adopt the guise of Shui Ta in order to keep her pregnancy a secret – until it seems that Shen Te has disappeared altogether. Convinced that the vile factory owner has murdered his friend, Wang the water carrier (Peter Woodthorpe) confides in the local barber, Shu Fu about Shen Te’s disappearance. Since Shu Fu (George Devine) is himself in love with Shen Te, and enlists the help of Yang Sun, who on learning that his lover is pregnant with his child, forces the police to arrest Shui Ta, who is brought to trial.

On hearing of Shen Te’s plight, the three wandering gods return to earth as her judges, and some irony is extracted from the respectable and the rich speaking on behalf of the tight-fisted capitalist. When Shen Te at last reveals herself as the impostor and the villagers discover her subterfuge, the gods airily insist that she is the one good woman they require to justify them leaving the world as it is, and they promptly return to Heaven.

Above: Peter (high stool to the left ) and the rest of the cast in a scene from the play.

In Retrospect

There were many scenes in this play, but there was little sense of movement. They illustrated what was intended to be geometrical clarity and the simplicity of a fairy tale – the rather dusty thesis that human beings, or it may be the world that they have created for themselves, are so constituted that it is virtually impossible for them to do good without trampling on others faces.

Below Right: Peter (lying on bench), with Dame Peggy Ashcroft and Peter Woodvine

The fable consists of deliberate simplifications, but the treatment is forbiddingly portentous. While the woman of Setzuan is a poor prostitute, her natural goodness is noticed by three deities who happen to be on a virtue-spotting tour of the world. Set up in a shop by the gods and bidden by them to remain good and yet to love, she finds that her goodness is likely to be her ruin.

The hand that is extended to the beggar is at once torn off. She tries to resolve the schizophrenic conflict that has been set up in her mind between sentiment and judgment, feeling and fact, heart and head, by dividing herself into two different people. She is She Te, the good woman; she is also Shui Ta, an invented cousin who protects her property from parasites including, not least, the young pilot with whom she falls in love and who proposes marriage.

When she discovers that she is to have a child by her lover, Yang Sun, the tight-fisted spiv takes over her affairs completely and adds to her property by viciously sweating labour and exploiting human credulity. As the woman she is merely a heroine; as the man, merely a villain; and both belong spiritually to the cartoon-strip of life.

The only moment in which Shen Te humanizes the heroine is when she proposes marriage to the hungry, unemployed pilot who is contemplating suicide. The young man’s despair, the tenderness of the woman, and the gathering thunder clouds over the trees all contrive to touch the scene with poetry. The reminder of the story is told, as in most Brecht plays, in a series of scenes and song – some brilliant, others not so, but which provide Peter with his first opportunity to sing live on stage.

By all accounts, the first act was the the worst, but this was worth enduring, as the second and third would give Peter the chance to bring himself to the fore as the shiftless pilot. Other notable performances came, of course, from Dame Peggy Ashcroft in the lead role of Shen Te, Peter Woodthorpe as Wang and George Devine as the affluent barber, Shu Fu.

| “One day at a rehearsal – remember Peter was playing Peggy Ashcroft’s lover, the flyer who got her pregnant – he said to me, “Robert, George (Devine) has asked me to slow my delivery down. The trouble is, you see, when I slow down my way of speaking, my voice gets lower and lower and when my voice gets lower, I get very, very sexy. D’you think that would be right for that scene? I’m not sure. What d’you think? Perhaps it would be.’ Peter made me laugh so much, I can still remember it.” Robert Gillespie |

Critics Comments

| “…Mr Peter Wyngarde plays the lover whose falsity deepens with appeals to his covertness, firmly and well…” The Times – Thursday, November 1st, 1956 “Peter Wyngarde is outstanding amongst many sound performers.” The Oxford Times “…Peter Wyngarde gives an R.A.F. type of interpretation of the self-indulgent airman…” The Guardian – Thursday, November 8th, 1956 “…Peter Wyngarde has avoided the squalor inherent in the whole thing. I do not see that he could have done it any better…” Punch – Wednesday, November 7th, 1956 “…Mr Peter Wyngarde managed both his romantic and his selfish side with tact and discretion.” The New Statesman – November 10th, 1956 “…Peter Wyngarde is an attractive, well-voiced rogue of a lover…” Theatre World – November 11th, 1956 |

4 thoughts on “REVIEW: The Good Woman of Setzuan”